Why Jewish Genealogy Requires Specialization

In modern-day America and Europe, equality before the law ensures that all citizens are treated equally under the law. While this ideal is not always upheld in practice, one of our nation’s guiding principles is that legal bureaucracy at least attempt to treat all citizens in the same way regardless of race, religion, or national origin. While we may take this ideal for granted, it was not always the case, either in this country or in others—a fact which has important ramifications for genealogy research.

In nineteenth-century Europe, many official records were created, maintained, and stored separately by religious grouping. Catholic birth, marriage, and death records were kept with Catholic records, Protestant ones with Protestant, and Jewish ones with Jewish ones. Moreover, various regulatory and legal frameworks were imposed differently on the different religious communities. As a result, genealogy research for each religious grouping has its own set of challenges. Due to the distinct treatment each population grouping received from centralized governments, a detailed historical background is necessary to be able to properly interpret historical documents. At the same time, Jewish genealogy frequently involves researching special sources which may be written in different languages than non-Jewish genealogy.

As this page and others will show, researching Jewish families requires a great deal of genealogical specialization.

Knowing Where to Find Information

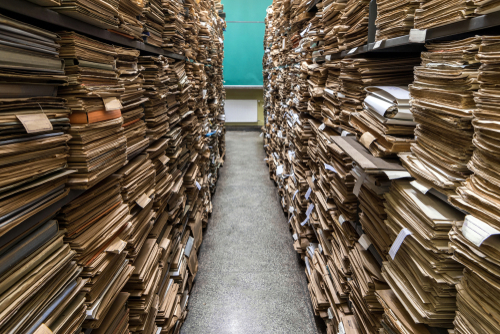

One of the first challenges in genealogy research is knowing where to look for relevant information. Because of the segregation of vital and other records in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Europe, many records in modern European government archives are still kept separately by religious grouping. In these archives, files with information concerning Jewish communities are held in entirely different groupings than those concerning non-Jewish populations. In addition to national archives, many important non-governmental repositories have developed around specific segments of the population. Significant numbers of them hold primary information highly specific to Jews. Developing an understanding of the extent and holdings of relevant repositories is a key component of genealogy specialization.

One of the first challenges in genealogy research is knowing where to look for relevant information. Because of the segregation of vital and other records in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Europe, many records in modern European government archives are still kept separately by religious grouping. In these archives, files with information concerning Jewish communities are held in entirely different groupings than those concerning non-Jewish populations. In addition to national archives, many important non-governmental repositories have developed around specific segments of the population. Significant numbers of them hold primary information highly specific to Jews. Developing an understanding of the extent and holdings of relevant repositories is a key component of genealogy specialization.

In addition to archives, many specialized sources exist which are relevant specifically to Jewish families. While a great number of indexes and databases exist to help genealogists with their research, the sheer multiplicity presents its own challenges. To be able to use them, it is necessary to know which databases exist, where they take their information from, and which ones would be the best suited to the research project at hand. Many of these databases are highly specialized, even within Jewish genealogy—focusing on specific geographic regions, time periods, or other topic of interest. One part of the specialization in Jewish genealogy is building up an understanding of the available research tools, including how—and when—to use each.

Geographic Factors

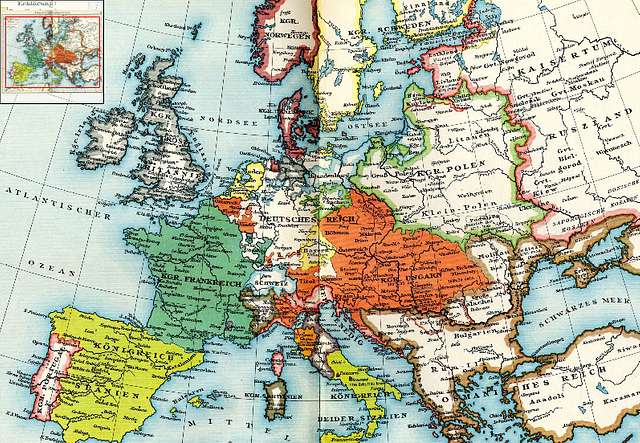

In Europe as in many other regions, national borders frequently changed, as did the names of cities and towns. As borders shifted, towns suddenly found themselves in different countries with different official languages. As a result, many towns were officially renamed. For example, the city now known as L’viv, Ukraine was known as Lwow prior to 1772, Lemberg between 1772 and 1918, and Lwow again between 1918 and 1945. Moreover, even without border changes, village, town, and city names frequently changed, both officially and unofficially. Furthermore, spelling of town names in many records is phonetic rather than official. As a result, the name of a town on a document may be very difficult to locate.

In Europe as in many other regions, national borders frequently changed, as did the names of cities and towns. As borders shifted, towns suddenly found themselves in different countries with different official languages. As a result, many towns were officially renamed. For example, the city now known as L’viv, Ukraine was known as Lwow prior to 1772, Lemberg between 1772 and 1918, and Lwow again between 1918 and 1945. Moreover, even without border changes, village, town, and city names frequently changed, both officially and unofficially. Furthermore, spelling of town names in many records is phonetic rather than official. As a result, the name of a town on a document may be very difficult to locate.

In the nineteenth century and earlier, Jews lived in specific areas within Central and Eastern Europe. When they migrated, those from certain countries tended to relocate to particular places. For example, late-nineteenth century Lithuanian Jews often migrated to Warsaw and other industrialized cities in eastern Poland, whereas those from Galicia often chose Vienna and Budapest. When leaving their national borders, Jews from most countries in Eastern Europe came to the United States, whereas the vast majority of Jews who ended up in South Africa had come there specifically from Lithuania. Specialized knowledge of historical migration patterns such as these helps genealogy researchers narrow down possibilities for where families may have gone to or come from.

Historical and Cultural Factors

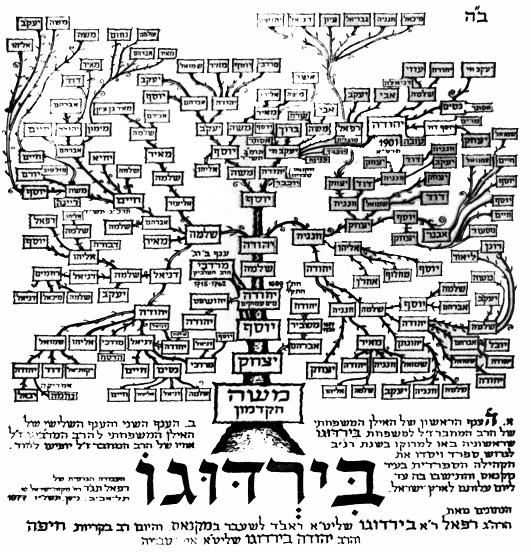

In addition to geography, Ashkenazi Jews maintained specific religious and cultural practices which drastically affect modern genealogy research. A good example of this is Jewish naming patterns. As is commonly known, Jews frequently name their children after deceased relatives. However, families in certain Jewish communities historically named children in predictable patterns. For example, Jewish families in certain regions consistently name their first son after the father’s father, their first daughter after the father’s mother, their second son after the mother’s father, and the second daughter after the mother’s mother. This pattern is more typical for Sephardi Jewish communities, but also occurred in some Ashkenazi areas.

In addition to geography, Ashkenazi Jews maintained specific religious and cultural practices which drastically affect modern genealogy research. A good example of this is Jewish naming patterns. As is commonly known, Jews frequently name their children after deceased relatives. However, families in certain Jewish communities historically named children in predictable patterns. For example, Jewish families in certain regions consistently name their first son after the father’s father, their first daughter after the father’s mother, their second son after the mother’s father, and the second daughter after the mother’s mother. This pattern is more typical for Sephardi Jewish communities, but also occurred in some Ashkenazi areas.

As a result of this and other naming conventions, multiple people in the same family—typically cousins—are often named after the same ancestor. Familiarity with historic Jewish naming practices can help prevent a great deal of confusion, helping to avoid the common error of mistaking two or more different people for a single person.

Moreover, Jewish naming practices also resulted in the same individual bearing multiple seemingly separate names. Traditionally, many Hebrew names are paired with other Hebrew names. For example, the name Binyamin is typically paired with Zev, and Yehuda with Aryeh. The reason for these specific name pairings goes back to a Biblical passage in which each son of Joseph was compared to a different animal.

By the later nineteenth century, Jewish society in Central and Eastern Europe was a highly multilingual one. A Jewish merchant in Galicia in the 1860s may have spoken Yiddish at home, Hebrew in the synagogue, Polish in business contexts, and German when dealing with government bureaucracy. Genealogical records reflect this linguistic profusion. Depending on the context in which it was used, a particular record might provide a person’s name—or its traditional paired one—in Hebrew, Yiddish, or the official language of the country or province of residence. Thus, records for Yehuda, Juda, Zev, Leib, or Lev Silverstein, or any combination of them, might actually all refer to the same person. By understanding the multiple variants of given names, researchers can avoid the common beginners’ error of mistaking one person for two or more different people.

By the later nineteenth century, Jewish society in Central and Eastern Europe was a highly multilingual one. A Jewish merchant in Galicia in the 1860s may have spoken Yiddish at home, Hebrew in the synagogue, Polish in business contexts, and German when dealing with government bureaucracy. Genealogical records reflect this linguistic profusion. Depending on the context in which it was used, a particular record might provide a person’s name—or its traditional paired one—in Hebrew, Yiddish, or the official language of the country or province of residence. Thus, records for Yehuda, Juda, Zev, Leib, or Lev Silverstein, or any combination of them, might actually all refer to the same person. By understanding the multiple variants of given names, researchers can avoid the common beginners’ error of mistaking one person for two or more different people.

Historical Context

As described in the section about professional genealogy standards, it is extremely important in genealogy research (or really, in any research) to use primary source documents. However, simply using them is not enough. It is critical to have enough historical background information to be able to properly interpret these primary source documents, many of which were written decades or even centuries ago in societies vastly different to those of today. A wide variety of circumstances affected people’s motivations for what to disclose to authorities—and, potentially, when to stretch the truth.

As described in the section about professional genealogy standards, it is extremely important in genealogy research (or really, in any research) to use primary source documents. However, simply using them is not enough. It is critical to have enough historical background information to be able to properly interpret these primary source documents, many of which were written decades or even centuries ago in societies vastly different to those of today. A wide variety of circumstances affected people’s motivations for what to disclose to authorities—and, potentially, when to stretch the truth.

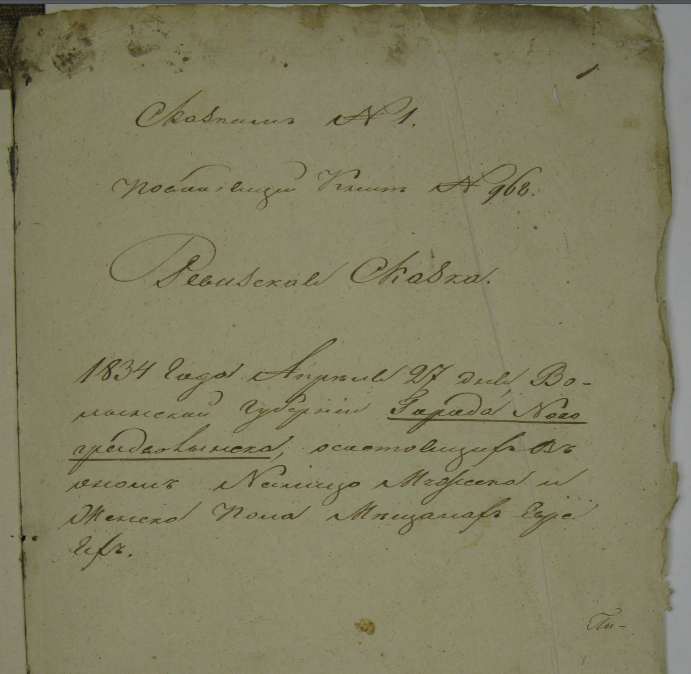

As just one example, one of the most important types of documents in Jewish genealogy research from Ukraine, Belarus, Lithuania, and other parts of the former Russian Empire are so-called “revision lists.” These documents list all members of a household along with their ages and sometimes their occupations. However, it is important to understand that they were created the purpose of military conscription.

Unlike in modern militaries, conscription in the Russian Empire was for a period of 25 years. Moreover, not only was conscription into the Russian army considered a lifetime commitment, but Russian Jewish conscription policies were often devised with the explicit intention of Christianizing the Jewish population. As a result, Russian Jews went to great lengths to avoid conscription—and had strong motivations to stretch the truth with the information they provided on revision lists.

As a second example, many genealogically useful documents were created for immigration purposes. During certain times in history, Jews who were desperate to immigrate might have been tempted to exaggerate certain things—including their relationship with sponsoring individuals. Without this specialized knowledge of historical context, one could be tempted to take information on these types of documents literally without realizing the particular need for careful scrutiny.

Professional genealogists who specialize in Ashkenazi Jewish genealogy know when to take documentary evidence at face value and when to take them with a grain of salt. For all these reasons, careful scrutiny of primary source documentation, along with a thorough grounding in the historical circumstances surrounding their creation, is an integral part of professional genealogy standards.

Turning Data into Stories

Knowledge of changing geography, cultural factors, and historical context are critical to interpreting primary documents. But your family is much more than just names and dates. They were real people with real hopes, fears, dreams, and ambitions whose lives were shaped by historical forces, events, and circumstances. As one example, the Polish Partitions in the late eighteenth century caused what had previously been a thriving, cohesive religious community to be split among three vastly different societies.

By the late nineteenth century, industrialization brought large numbers of people, both Jews and non-Jews, out of their ancestral villages and into cities—although it affected each of the three countries ruling former Polish lands in distinct ways. Changes in European society brought on by the Industrial Revolution helped lead the way to Jewish Emancipation, bringing full civil rights in Germany, partial civic integration in Austria, and profound ambivalence in Russia. The resulting changes in Jewish society redefined the religion and its relationship with the wider world—themes which are still central to Jewish life today, a century and a half later.

Summing Up

Reconstructing your family’s history is dependent on understanding its socio-historical context. Correctly identifying locations named in genealogical documents relies on a deep understanding of historical geography, while research conclusions can only be accurate if one possesses the requisite understanding of cultural factors and historical context necessary to properly interpret primary source documents. Moreover, a thorough grounding in the historical context specific to Ashkenazi Jewish families can help your genealogy come alive, turning names and dates into real people and the stories that make them breathe, walk, and dream. Read on to discover a few of the many stories I have uncovered for clients just like you.