Who Am I?

Recovering Lost Roots: One Researcher’s Quest for Jewish Family History

Joshua Grayson, PhD

As with many people reading genealogy blogs, I have always been fascinated by family history. Ever since I was a child, genealogy connected me with my grandparents. Even as a child, I was always so happy to talk with them about our family’s history—although back then, I had no way of knowing that it would become an obsession that would change the course of my life.

Whenever I was lucky enough to visit my grandparents at their house on Long Island, I would always stop to gaze at a family portrait placed at the bottom of the staircase. Taken in 1904, it depicts my grandfather’s grandparents and the first five of their ten children—including my great-grandmother at the age of 11. The picture, with my great-grandmother’s kindly wisdom beyond her years, my great-great grandmother’s gentle warmth, and my great-great grandfather’s dignified stolidity (not to mention his enormous handlebar moustache) had always captivated me. To my childish imagination, I was sure I could almost feel their presence looking over me and their other descendants. I was so curious about the people in that picture and what their lives may have been like.

After I could tear myself away from the photograph, my grandfather and I would frequently discuss family history together. He told me how his grandfather Simon had migrated from Lemberg, Austria (today’s L’viv, Ukraine) to Munich, Germany in the 1890s, and about Simon’s father Israel Penzias who had owned a furniture store in Lemberg. Listening to these stories, I wondered who came before them even, who Israel’s parents and grandparents were, where in the depths of time we originated from.

Then, my grandparents would tell me stories of their own lives, and I would hear about my grandfather heroically rescuing other Jews from Germany through the Aliya Bet, my grandmother’s experiences on the Kindertransport, the two of them listening to radio broadcasts of Winston Churchill inspiring a nation, their marriage in London in the middle of the Blitz with bombs falling all around them. Although I didn’t realize it at the time, coming from a family like this perhaps made it inevitable that my interest in genealogy would further blossom.

From PhD to Genealogist

While I had always been captivated by family history, I have also maintained another lifelong passion: classical music. I have studied classical piano since the age of three, given more performances than I can count, studied for six years at the Juilliard School in New York, and attended the prestigious Indiana University Jacobs School of Music for college. After graduating with bachelor’s degrees in piano performance and mathematics, I enrolled in a PhD program in historical musicology at the University of Southern California. I am happy to say that I have completed my coursework, successfully defended my dissertation, and am now a doctor – although please don’t ask me to see any patients!

My doctoral program did not only teach me about music. In fact, during my many years in higher education I acquired a wide assortment of research skills. The skills I acquired to gather historical evidence, critically evaluate sources, develop knowledge, and effectively communicate my ideas about music have an astonishingly wide variety of other applications—and are particularly well-suited to genealogy. Using modern research techniques, I have delved deeper into my family’s history than I ever would have thought possible, uncovering and reconstructing information that otherwise might have been lost forever.

Digging into the Records

Burrowing into electronic records in various databases, I learned the names of some of my ancestors from as far back as more than 200 years ago—and discovered that my family had been living in Lemberg (where my grandfather told me his grandfather was born in 1869) at least since 1805. Two individuals from that time held the family surname—Baruch and Moses Penzias. Perhaps they were brothers, and perhaps one of them could have been Israel’s grandfather. Already some of my childhood questions had been answered, yet they tantalizingly raised new questions.

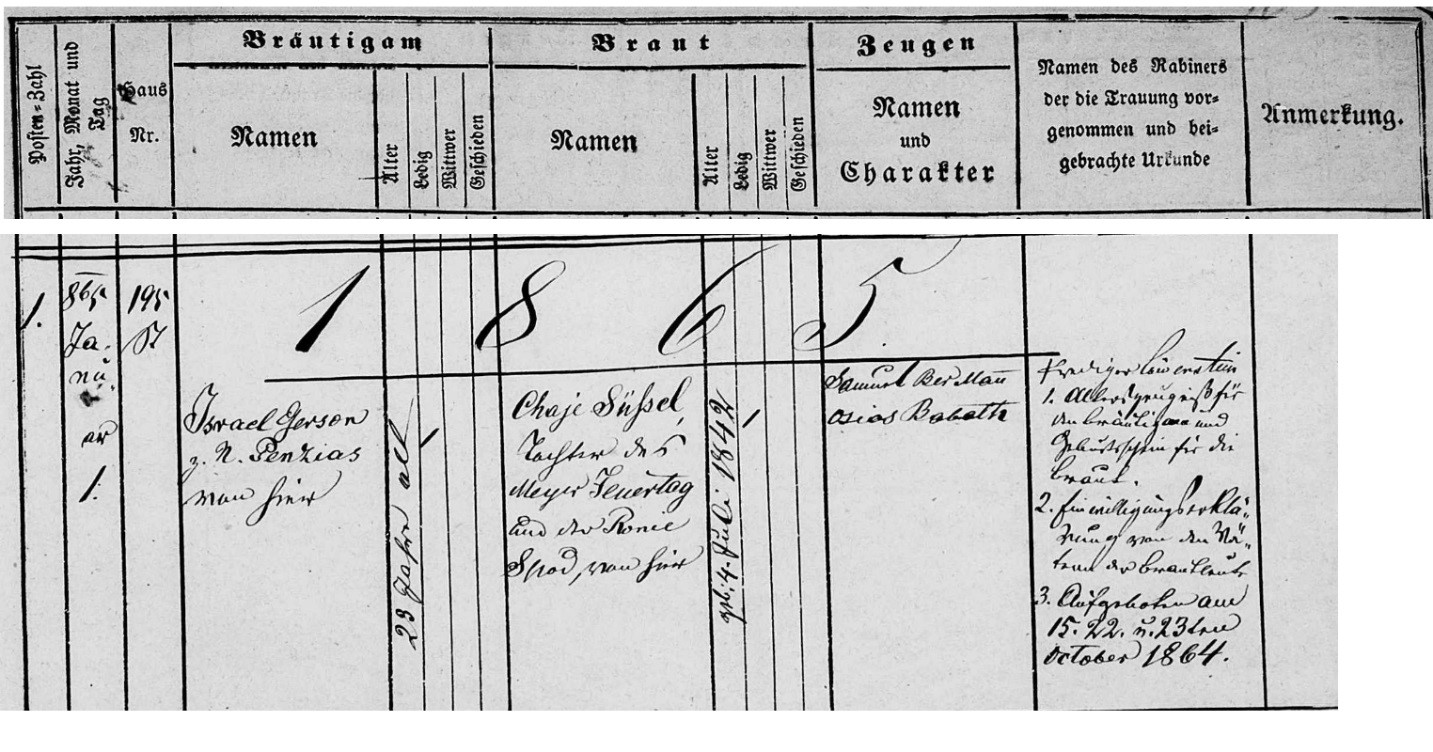

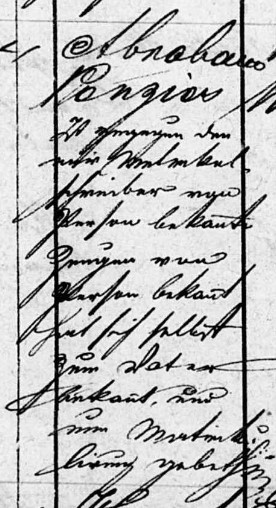

My next stop was the Mormon Family History Center, on the west side of Los Angeles. As part of a project to document and protect the family heritage of millions of people in hundreds of countries, the Mormons have preserved hundreds of millions of genealogical records spanning centuries. Once I found the records I was looking for (not an easy task), I was ecstatic to discover that they held significantly more information than the Internet databases I had been using. Since the area where this part of my family originated was part of the Austrian Empire at the time, the records were in German.

Unfortunately, there was a problem: German handwriting in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was completely different from modern German handwriting. In fact, many of the records I found looked more like squiggles than any kind of writing I could recognize. Called “Kurrentschrift,” without special training it is almost completely illegible even to modern Germans. Rather than giving up, I turned to a variety of resources to help me overcome this barrier. I had studied German for three years in high school, so I felt confident that I could eventually be able to decode these mysterious documents.

After some practice tutorials I found online and an inordinate amount of patience, trial, and error (more error than trial), after several months I was eventually able to make out these weird squiggles in my ancestral documents. It turns out that beneath my 4x great grandfather’s name in one of them is the word “Eierhändler,” meaning egg merchant! Although most records did not list professions, I found that one of my relatives during the mid-nineteenth century changed

professions at least twice: from a schoolteacher in 1830 to an upholsterer in 1832 to a horse merchant in 1838. Each new discovery seemed to lead to more interesting tidbits. By now I was hooked!

Next, I turned to historical newspaper and directory research. I was truly astonished by some of the things I found! For instance, I learned that my family donated a significant sum to support the Austrian war effort in 1795, and donated again fifty years later to contribute to rehabilitation efforts after a devastating flood in the 1840s. Moreover, I was ecstatic to discover that I am related to a nineteenth-century rabbi, an esteemed philosopher of the nineteenth-century Jewish Enlightenment movement, the vice-president of the First International Zionist Congress, and a NASA scientist who designed lunar landers! Other historical documents I found let me push back my knowledge of some branches of my family back to 1796, 1787, 1733, even approximately 1700!

From German to Russian

My grandfather never knew his father’s parents; both had passed away before he was born. His father had not had a close relationship with them, so our family history on that side had always been a mystery. All we knew was that my grandfather’s grandfather Wolf Rubin Grajewski married a woman named Frieda Czak, came from Warsaw, was a tobacco merchant, and lived in eight different cities in Germany before settling down in Stuttgart. Due to the name, we had always assumed that his ancestors had come from Grajewo and had migrated to Warsaw at some point in the nineteenth century.

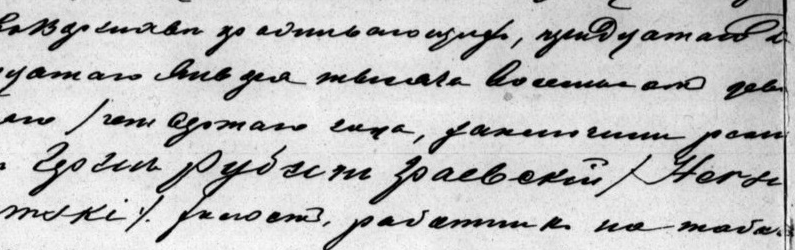

Using another Jewish genealogical database, I found a marriage record for a Hirsch Rubin Grajewski and Fraida Krzak. Because much of Poland had been controlled by Russia during the nineteenth century, the record was written in Russian. I studied Russian in college and spent a semester in college studying abroad in Moscow, so I am proficient in speaking and reading Russian in addition to German. Unfortunately, pre-modern Russian cursive presents very similar challenges to the modern researcher as pre-modern German cursive. Namely, thanks to a 1917 spelling reform there were several additional letters in the Cyrillic alphabet I had not learned, several other letters had multiple handwritten forms I had not encountered, and many words were spelled slightly differently. Just as I had done with the German, I embarked on a months-long intensive self-study of this old Russian handwriting system. Eventually I was able to read it. What I found was astounding!

Hirsch and Fraida’s marriage record states that Hirsch was a worker at a tobacconist, so I knew that these were the same people—apparently when he moved to Germany, he changed his name from Hirsch to Wolf, which perhaps tells something about his personality (the name Hirsch means deer; Wolf means wolf). The marriage record also included much more! It gave both of Hersch’s parents’ names, both of Fraida’s parents’ names, Fraida’s mothers’ maiden name, and even the street addresses in Warsaw where they were living.

Being able to read 19th-century Russian cursive (a rare ability, even for professional genealogists) proved to be the key that unlocked this entire branch of my family. Each new record I found led me to new, sometimes surprising information. First, I was able to find Hirsch’s parents’ marriage in 1865 in Radziejow, a small town approximately a hundred miles west of Warsaw. I also found that both Hirsch’s and Frajda’s fathers had been soldiers, and that Hirsch’s father Josek received a bronze medal from Czar Alexander Nikolaievich (Alexander II) for services rendered to the crown during the Crimean War.

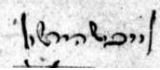

Fraida’s mother’s family came from a stetl a short distance north of Lublin; her father Berek Kitmacher and grandfather Leibush had been glaziers there. I even found Berek’s birth record from 1812, which provided information on his father Leibush and his grandfather Hirschel. The document even had the handwritten Hebrew signature of Leibush, my great-great-great-great-great grandfather! I made many more discoveries than I can possibly describe in one place; keep reading my blog to learn more!

found Berek’s birth record from 1812, which provided information on his father Leibush and his grandfather Hirschel. The document even had the handwritten Hebrew signature of Leibush, my great-great-great-great-great grandfather! I made many more discoveries than I can possibly describe in one place; keep reading my blog to learn more!

The story of my family that I have compiled—an epic story spanning hundreds of years on three continents, a story that weaves together egg merchants and bakers; Austrian coppersmiths and Russian soldiers; Enlightenment scholars, European painters, and Jewish heroes—is really the story of me. And more than that, it is the story of us.

From Researcher to Founder

The information I discovered about my family changed my life. Knowing so much more about who I am and where I came from has meant more to me than words can express. But helping myself is only one small part of a much larger journey. I feel extremely excited and passionate about using my skills to help others, so I decided to start Lost Roots Family History. My company is devoted to helping other Jewish families reconnect with their roots, discover their past, engage with the present, and preserve their heritage for the future. In researching your family’s history, I can offer the following skills and talents:

· Advanced database search techniques

· Primary source research

· pre-1940 German cursive handwriting (“Kurrentschrift”)

· pre-1917 Russian cursive handwriting

· Hebrew: print, cursive, and Rashi script

· Historical newspaper research

· Historical city directory research

· Holocaust research

As I mentioned before, reading ability in Kurrentschrift, pre-Revolutionary Russian, and Rashi script are rare, even in genealogy circles. The ability to read all three of these is something fairly unique—yet it can be integral to research for Jewish families. If your family is anything like mine, you will likely have branches in several different countries. A multi-lingual researcher who can conduct research in many of these locations can be a significant benefit to such families. I am also in the process of attaining professional genealogical certification.

Reconstructing whatever small fragments of information our ancestors have left behind—names, dates, occupations, addresses—is a way of keeping the past alive. It lets us honor these people long after all those who once knew them have passed on. Ultimately, understanding who we are, how we got here, and where we fit in the grand sweep of history can help us with our task, which is everyone’s: maintaining our unique heritage as a personal, vital force in the world. It truly is a torch we inherited from our ancestors and that we are destined to carry on from one generation to the next.