What Can You Expect a Professional Genealogist to Find?

In one of the most famous openings of nineteenth-century literature, Russian author Lev Tolstoi began his novel Anna Karenina with the line, “All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” While this has a certain undeniable poetry, it nevertheless is an oversimplification. Had Tolstoy been a genealogist, he undoubtedly would have realized that all families, happy or otherwise, are unique. Every family has its own particular size, characteristics, and personal circumstances. It is therefore no surprise that no two genealogy projects are exactly alike.

In my multiple years as a professional genealogist focusing on Jewish families from Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, and Ukraine, I have uncovered many fascinating stories. While it is impossible to say with certainty what any one genealogy project will uncover, the stories in this section may help give you an idea of the kinds of things I may be able to discover for your family.

A History Reclaimed

As the daughter of a Holocaust survivor, Miriam was always bothered by the fact that she never knew about her father's family. Although she knew that he was originally from Lublin, she always wished that she could have known more about her family's story, origins, and heritage.

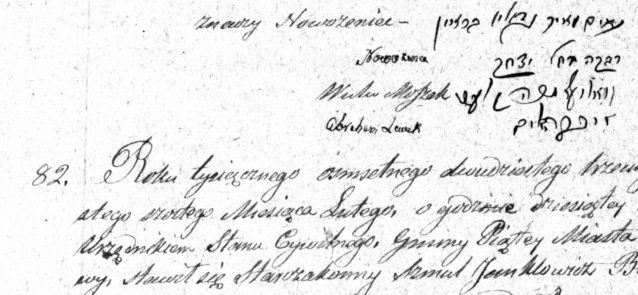

Research by Lost Roots Family History uncovered more about her family story than she had ever thought possible. The story begins with her great-great-great-great-great-grandparents Lejzor and Malka, who were born around the year 1750. Their two grandsons Lejzor (1805 - c.1856) and Eliasz (1815 - c.1900) worked in the lumber industry as sawyers, moving around a great deal and settling in numerous villages throughout rural Lublin province. They were born in the tiny village of Chrzanow, today a hamlet containing only four houses.

The family continued to grow and develop, spreading out to numerous towns and villages in the mid-nineteenth century. By the 1880s, Miriam's great-grandfather had settled in Lublin, becoming a shoemaker there. His daughter, Miriam’s grandmother Miriam Brandl, was born in Lublin in 1889. Many of her family members lived in the city's old town, while wealthier relatives settled in more upscale districts. At the same time, many descendants of other branches of the family had congregated in the town of Opole Lubelskie, not far from the Vistula River.

During the Holocaust, many of Miriam's relatives were murdered by the Nazis; research by Lost Roots Family History has given them names and faces. A number of her relatives distinguished themselves during this time, heroically standing up for their community and fighting the Nazis. One of Miriam's family members, Avraham, joined an underground resistance cell based in Krakow, while another relative joined the Red Army and received a medal of valor.

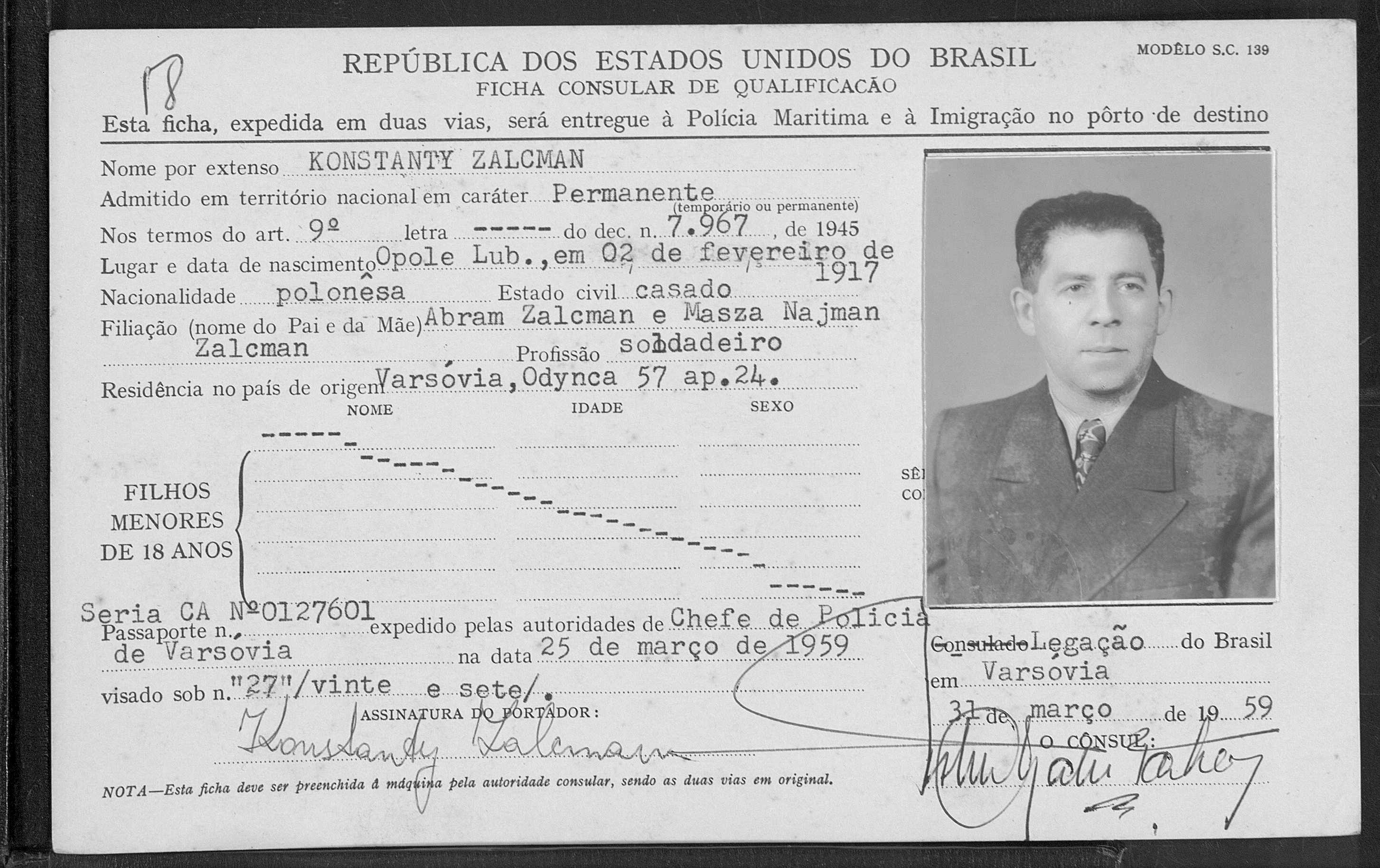

In more recent times, Miriam's family has spread far and wide. My research has revealed family members across the United States as well as in São Paolo (Brazil), Guatemala City, Mexico, Israel, and Tunisia. Wherever they have gone, they have carried with them their ancestors’ traditions along with their spirit of adventure, independence, and pride.

Starting from knowing virtually nothing, Miriam now has knowledge of ten generations of her family. Uncovering her family story and connecting with relatives she never knew she had has made an enormous difference in her life. In her own words, “I have a history!”

Deep Urban Roots

Allison had grown up knowing a fair amount about her family history but always wanted to know more. She remembered hearing that some of her ancestors had sold brass and copper parts for carriages in Warsaw, and that her grandmother’s brother had served in the Russian army. Still, she wondered what else could be found. She began investigating on her own but found the prospect of researching her family in Europe daunting. Without a knowledge of the languages and scripts involved, she couldn’t get beyond the most basic facts.

Lost Roots Family History investigated several branches of Allison’s family, including one that I traced back to approximately 1735. According to documentary evidence I uncovered, Allison's family had lived in the city of Warsaw for more than a hundred years prior to the Holocaust. Additionally, I located another branch of Allison’s family in the village of Lasek, and traced it back there as early as 1804.

Allison’s family members in Warsaw took part in a wide variety of occupations. Many members of her grandmother’s mother’s family worked as hat makers, an occupation the family practiced from the 1700s up through the twentieth century. During the same period, many of her grandmother’s father’s family members worked as coppersmiths and metal workers. Many ended up going into their own businesses selling their iron wares.

Using nineteenth- and early twentieth-century historical business directories, Lost Roots confirmed some of the family legends. After locating her great-grandfather’s iron bed store, I also discovered that the family had owned an iron furniture and baby carriage factory, a paper store, a grocery store, and a wholesale store. In more recent times, not only did I confirm Allison’s grand-father’s brother’s military service with the Red Army, but I discovered that he was awarded a medal of honor.

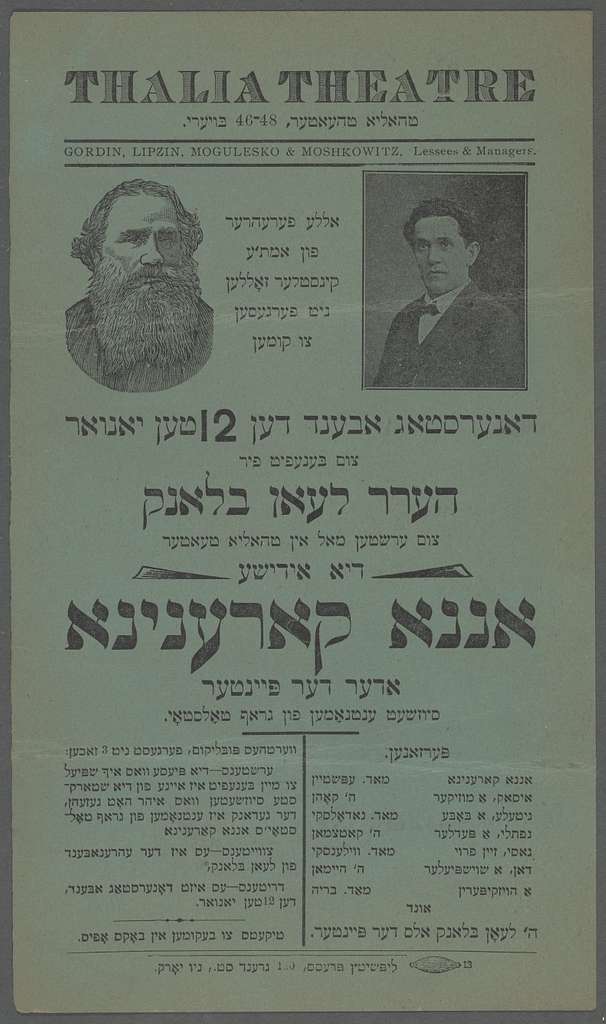

Although most of Allison’s family perished in the Holocaust, Lost Roots discovered that one of her great-grandmother’s distant relatives moved to New York in 1920. This relative’s son continued in the hat making business, carrying on in the New World the family’s traditional occupation they had practiced in Europe for more than a century. Today, many of this person’s descendants live in the Southeastern United States, where one of them is a professor emeritus at a prestigious university in New Orleans.

Through Lost Roots Family History’s research, Allison had confirmed many of her family legends, learned more than she had ever thought possible, and came into contact with relatives she never knew she had.

Unravelling a Mystery

Like many Holocaust survivors, Nina’s mother Rose rarely talked about her experiences or her family history. In fact, Nina did not even know the names of her grandparents. Even more, exploring this side of her family began with a mystery.

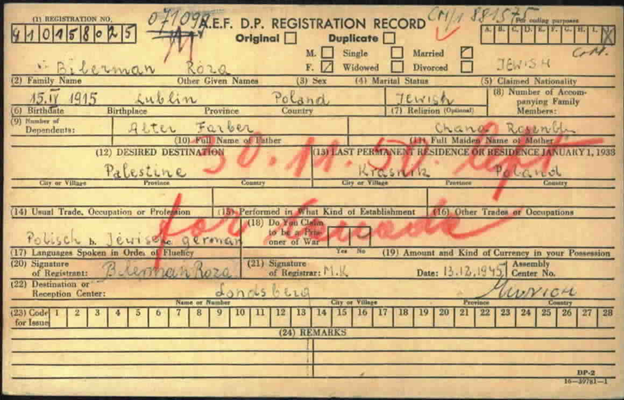

Investigating Jewish families who survived the Holocaust often begins with documents filed with the International Tracing Service (ITS). Yet ITS research on Nina’s mother yielded two different displaced persons registration cards which provided very similar yet contradictory information. The two cards indicated the same first and last (married) name, birthplace, town of residence, and birthday. However, the two birthdays were exactly six years apart (1915 vs. 1921). The most confusing part of the cards was that they named two different sets of parents—one Alter and Chana Farber, the other Isaac and Necha Akerman.

It is highly unlikely that there actually were two different people with the same first name, born in the same city, who moved to the same town, married men with the same last name, and shared the same birthday. Yet if the two cards were for the same woman, why did she indicate two different sets of parents and two different birth years? Which card was correct? If the other two people were not actually her parents, who were they?

Researching vital records in Lublin, the birthplace given on both cards, led to the discovery that Alter and Chana Farber, the set of parents given on the first displaced persons registration card, had had a baby in 1884. As such, they must have been at least 50 years old by 1915, the earlier of the two given birth years. They could not possibly have been Rose’s birth parents.

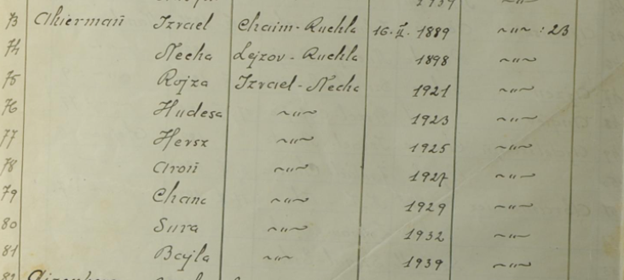

A list of Krasnik ghetto occupants compiled in early 1945 shed more light on the mystery. The document lists Rose as having lived with parents Israel and Necha Akerman—information which almost exactly matches that provided in one of the two registration cards (which had her father’s name as Isaac). From the same document, it turned out that Alter and Chana Farber’s son, Jacob, had lived in the same house as Rose’s future husband Chaim. Immigration records show that when Rose and Chaim immigrated to America five years later, it was Jacob Farber who sponsored them. Rose had probably altered her age and listed Jacob’s parents as her own in one of the two displaced persons registration cards in hopes that it would eventually enable him to sponsor her as a relative.

Further research in Lublin vital records located the birth record of Isaac Akerman, born on February 16, 1899. The Krasnik ghetto list gave the birth date of Rose’s father “Israel” Akerman as February 16, 1889 (exactly ten years earlier). It thus appears that Rose’s true parents were Isaac and Necha, and that the information in the Krasnik list had been slightly inaccurate.

Combining clues from all available sources allowed me to determine the precise identities of who Rose’s parents. Using this information as a springboard for further research, Lost Roots Family History reconstructed the history of Nina’s family back to her great-great-great-great-great-great-grandfather Abram (born c.1750). Tracing the family forward into modern times, I was able to connect her with distant relatives living in New York and Argentina.

Summing Up

The information I uncovered about these three families allowed me to dig up their deep pasts and connect them with family in the present. While all families are different and the information I might find about your family could vary greatly, these examples are illustrative of the kinds of stories I have been able to bring to life about my clients’ families. To learn more about how genealogists operate, feel free to read about hiring a professional genealogist or why specialization is necessary for Jewish genealogy.

If you are interested in hiring me to research your family, please feel free to schedule a research appointment.