Working on a Historic Treasure -- Prague Old Jewish Cemetery (Part 4)

In my last few articles, I described a large project on the Prague Jewish Cemetery I am undertaking in conjunction with E. Randol Schoenberg. I am happy to report that this exciting project is ongoing and that I am making solid progress. As of November 2019, I am approximately 30% through the 420-page Popper manuscript, with more entries added every day. I am also making fascinating discoveries—stay tuned to my Virtual Museum page to learn about some of the more remarkable people I have uncovered.

As captivating as it is, my work on the cemetery project has also brought up a number of unexpected challenges.

Challenge 1: Hebrew Dates and Numbers

In both sources I am working with (Popper’s book and Hock’s manuscript), dates are given according to the Hebrew calendar rather than the Western one. In addition to using different months, the Hebrew calendar year is widely different from the Western year—in fact, it is currently (November 2019) the year 5780 in the Jewish calendar. Moreover, the new Hebrew year begins not on December 31 but on Rosh Hashanah, which typically falls in September or early October. Finally, the Hebrew calendar is based on cycles of the moon—whereas the Western one is based on the earth’s motion around the sun. As a result, the Hebrew year is eleven days shorter than the Western year. To prevent holidays from drifting out of their proper season, an extra month is periodically added to the Jewish calendar.

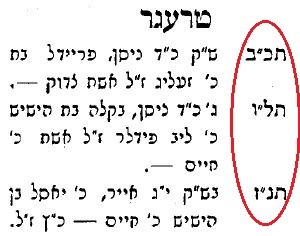

As an additional complication, Hebrew dates are written in Hebrew numerals rather than Western ones. Like Roman numerals, Hebrew assigns numerical values to letters of the alphabet and uses letter combinations to arrive at higher values. Fortunately, the Hebrew numeral system is much simpler than Roman numerals. Nevertheless, it does require some getting used to.

Thus, my first major challenge in creating the database is being able to quickly translate from Hebrew dates in Hebrew numerals to Western dates in Western numerals. For simplicity’s sake, I ignore the different starting dates and yearly lengths, treating each Hebrew year as though it ran from January 1 through December 31. I then mentally translate from Hebrew numerals into Western ones and convert the result from the Hebrew year into the corresponding Western date. With enough practice, I have developed the ability to do the conversion quickly and effortlessly in my head.

Challenge 2: Typing in Hebrew

Popper’s manuscript and Hock’s book each contain large amounts of information in Hebrew. Although I am translating this information into English in the database, I have decided to include the original Hebrew wording along with my translations. However, because it uses a different alphabet, typing in Hebrew is completely different than in English. Since I unfortunately do not have access to a Hebrew keyboard, entering the information in Hebrew posed a huge challenge.

First Technique: Character Map

All modern versions of Windows come equipped with Character Map, a basic tool for entering non-Latin characters into the computer. Fortunately, this tool includes Hebrew letters. To insert them, open the Character Map program, scroll down to the Hebrew letters, and select the letters you want one at a time. Once you have spelled out the text you want to enter, copy it from Character Map and paste it into your document or program. Unfortunately, this method is clumsy and highly inefficient. To get through the vast amount of information in the cemetery documentation, I needed a better way to input Hebrew.

Second Technique: Training Myself to Type

Thanks to a very wise fifth-grade teacher, I learned proper touch-typing technique from a very early age—for English. Due to this training, when typing in English my fingers instinctively “know” where to go on the keyboard. I can type anything quickly without ever having to look for the letter. What I needed was a way to be able to replicate that in the Hebrew.

When I was learning English typing, my teacher stressed the importance of looking up at the computer screen rather than looking down at the keyboard; she knew that we would never develop this muscle memory if we continued to rely on looking down at our fingers. Reproducing this in Hebrew required a degree of resourcefulness because I was working on my own and did not have a Hebrew typing program of any kind. However, I was able to come up with a novel solution that worked quite well. My solution involved the use of an online Hebrew-English dictionary

Unlike printed dictionaries, online language dictionaries require users to type the words they want to look up. Because many users lack foreign-language keyboards, online language dictionaries almost invariably include “virtual keyboards.” Like Character Map, these tools allow users to form words by selecting letters on their computer monitor. However, virtual keyboards are set up identically to physical keyboards in the target languages rather than alphabetically as in Character Map. Thus the virtual Hebrew keyboards found on Hebrew-English language websites like Morfix (https://www.morfix.co.il) served as the perfect tools to enable me to train myself to type in Hebrew.

The first step was to install Hebrew onto my laptop using Windows language settings. Once that was done, I was able to input Hebrew letters without requiring the use of Character Map. However, the labels on the keyboard keys still were in English, so I did not know what letter I would be typing until I had already typed it. To train myself in Hebrew typing, I typed on the laptop while looking up at the virtual keyboard on my desktop monitor.

Immediately, I was much faster than using Character Map, although still not fast or accurate enough. After about a week of practice, I started to remember where the letters were—at first a few of them, then many of them, and finally almost all of them. After a few weeks, I got to the point where I could simply type without having to think about where each letter was—just as I had gotten with English typing all those years ago. I was finally able to enter the Hebrew information into the database accurately and efficiently.

Challenge 3: Interpreting Hebrew Names

Due to a variety of factors inherent to Hebrew, reading some of the names I found in Popper’s manuscript offered several challenges. As a result, the process has been more like interpreting than translating or transliterating.

Hebrew Orthography

When reading in Hebrew as in any other language, one can usually tell from the context which word or pronunciation is intended—although inconsistencies do occur from time to time. However, when reading proper names—particularly unfamiliar surnames—there is no context. Sometimes deciding which name Popper intended can be a judgment call.

For several reasons, Hebrew writing (not including prayer books or children’s material) can be quite ambiguous. First, Hebrew does not normally indicate vowels. Secondly, four Hebrew consonants (five in the traditional Ashkenazi pronunciation) have two distinct pronunciations each. Thus, the names Falkeles, Flekels, and Pilkels are all written identically. Even worse, Popper often fails to indicate spaces between words. Luckily, five Hebrew letters are written differently when they are the last letter of a word, which can sometimes help identify word beginnings and endings. However, this is not always sufficient to avoid ambiguity.

Naming Conventions

In sixteenth-century Prague as in later European Jewish communities, surnames frequently carried meaning. Many surnames denote occupations or religious roles, while others signify cities, towns, or geographic areas. As a result, when encountering them, it can be very difficult to determine whether they are surnames or descriptions—especially given that since Hebrew lacks capital letters, it does not have any means to distinguish between proper and common nouns. For example, in a document that sometimes lists occupations and in which not all individuals have surnames, “abraham smith” may indicate either that the person was named Abraham and worked as a smith or that his name was Abraham Smith. Similarly, the word “shamemsh” in the Popper index may indicate that the person was a shammesh (synagogue helper) or that his last name was Shammesh. Sometimes the context is clear enough to tell which is intended, but not always.

In fact, sometimes I disagree with Popper. Because his document is bilingual in Hebrew and German, I can gain an understanding of how he interpreted the tombstone inscriptions he was transcribing. While the context may be ambiguous, sometimes the Hebrew text clearly shows that the word is a description rather than a surname. For example, a person may be described in Hebrew as “shammesh in the Altneu Synagogue.” In some instances, Popper included the Hebrew text but treated the word “shammesh” as a surname. Thus, I am frequently forced to make editorial decisions.

Hebrew Grammar

Unlike English, in which prepositions and articles are separate words, Hebrew forms them by adding prefixes to the beginnings of nouns. For example, “b-“ before a word indicates the preposition “in,” “m-“ means “from,” and “h-“ denotes “the.” Unfortunately, sometimes nouns and names can actually begin with one of these letters. When encountering a word beginning with one, it can be very difficult to determine whether the first letter is a prefix or a part of the name. This can be especially difficult for names that start with the letter M—for instance, seeing the word “Marla” might mean the name “Marla” or it might mean that the person was from a town called “Arla.”

By spending enough time with Popper’s manuscript and by comparing it with the Hock and especially with Beider’s index of surnames, I was eventually able to develop a familiarity with many of the names. This has frequently allowed me to recognize names even when written ambiguously. However, once again I must often make editorial decisions.

Why Does This Matter?

From my other life as a musician, I am very familiar with the old adage, “How do you get to Carnegie Hall?” As a genealogist, practicing my skills is what is allowing me to overcome the many challenges I face and to succeed in this very important project. When analyzed, the data I collect will yield fascinating insights into this pivotal Jewish community.

Beyond genealogy, I hope that my work can inspire you, my readers, to work hard at whatever challenges you face in life. Whatever your vocation, please continue to improve yourself, learn new skills, and never back away from a challenge—no matter how intractable it may seem. You will almost always be happily surprised by the results.

Add new comment