Working on a Historic Treasure -- Prague Old Jewish Cemetery (Part 2)

In my previous blog article, I provided some background information on the world-famous Prague Jewish Cemetery, and on some of the various attempts to document it. In today’s post, I will discuss my own efforts.

An Important Effort

For a variety of reasons, the Prague Jewish cemetery is particularly important to the study of Jewish genealogy and history. In spite of this, not much is generally known about the individuals comprising the historic Prague Jewish community due to the often insurmountable difficulties of the source material.

One of the main reasons the Prague cemetery is so important is its historicity. Official Jewish vital records in most of Europe—even in larger cities—only go back to about 1800. In smaller towns, records might only be available starting from the 1860s. While cemeteries existed in all Jewish communities, most were destroyed during or after the Holocaust; few Jewish cemeteries were documented prior to their destruction. By contrast, the Prague cemetery was documented in its entirety. The records from this cemetery contain information about people who lived in the late medieval, Renaissance, and early modern periods. To have documentation this extensive on Jewish individuals and families going back to 1439 is extremely rare.

Even more importantly, Jews in Prague took family surnames long before those in other parts of Central and Eastern Europe. While almost everywhere else (other than Sephardim and a few prominent rabbinical families) Jews identified themselves only by first name and father’s name, Prague Jews used hereditary last names as early as the 1500s. This could make it possible to construct family trees that stretch back hundreds of years earlier than elsewhere.

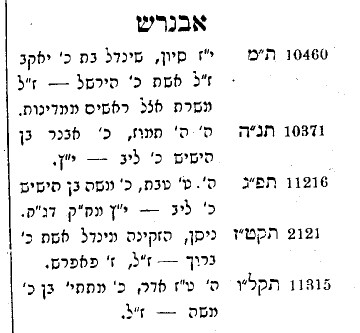

Unfortunately, things are not as simple as that. While extensive documentation of this cemetery exists, it offers considerable challenges to modern researchers. Although some of Hock’s work (see previous blog) has been published as a book, this book is far from complete and represents only a small amount of his total work on the cemetery. Additionally, Hock’s work is written exclusively in Hebrew (except for an introduction in German), and it is printed in Rashi typeface. It is safe to say that few genealogists are fluent in Hebrew, and even fewer are able to read Rashi print.

Popper’s manuscripts (again, see previous blog) offer much more detail, particularly in the marginal notes. However, they are even more difficult to use than Hock. Although most names in Popper are in German, critical information is written in Hebrew—and in a very hard-to-read Hebrew script. Moreover, although Popper’s manuscripts have been digitized, they are only available in photographic form. Neither Popper nor Hock are computer searchable at present.

To help overcome these challenges, I have been contracted by E. Randol Schoenberg to create a fully searchable spreadsheet with the information contained in the Popper name index. One of the most prominent Jewish genealogists in America (and a former president of the Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust), Schoenberg has long maintained an interest in the genealogy of the Prague Jewish community. Hidden within Popper’s 420-page index is a huge wealth of information about one of the most important Jewish communities of early modern Europe.

Step 1: Improve Image Quality

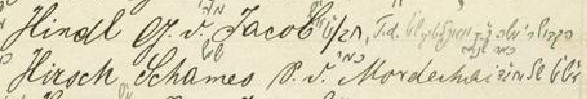

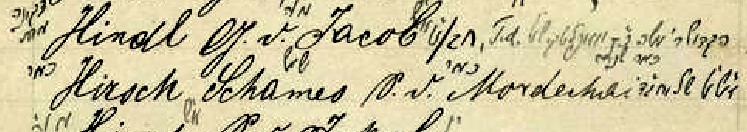

Like any monumental undertaking, work on this project proceeds in stages. The first step goes a long way to addressing the first problem of readability. Popper’s manuscript features notes written in the margins which contain extra information that is critical in constructing family trees out of surname lists. The problem is that this information was written in pencil in the 1880s, nearly 150 years ago. Consequently, it is faded and extremely hard to read.

The solution I have come to is GIMP (GNU Image Manipulation Project), a highly powerful open-source photo editing software. Using GIMP, I utilize image preprocessing techniques to significantly enhance the readability of the scans. This is particularly helpful in reading the faded pencil notations.

With the image quality improved as much as possible, it is now time to move on to step 2.

Step 2: Compare Side-by-Side with Hock

In spite of what can be achieved with GIMP, many of the handwritten notations are still incredibly difficult to read. Popper’s handwriting is somewhat nonstandard, with some letters written in forms I have never encountered before—even in other 19th-century handwritten Hebrew documents. In fact, Popper uses four separate handwriting styles: one type of cursive for the notes, another type of cursive for most dates (written in Hebrew numerals), regular Hebrew print occasionally for a few dates, and handwritten Rashi type for the Hebrew spellings of surname headings.

Even worse, Popper’s writing is tiny, and the scan qualities are not always sufficient to zoom in enough (although I am incredibly grateful to the Jewish Museum in Prague for creating them and for making them available). Moreover, spacing between words is inconsistent and sometimes missing. To make matters even more challenging, comments can overlap with each other or with the names—sometimes when seeing a small stroke as part of a letter, it can be very hard to determine which language and which alphabet it is in. Finally, as has already been seen, Popper’s manuscript has been damaged in some sections and information has been lost. For all these reasons, Popper’s manuscript is extremely difficult to read, and many potential ambiguities come up.

Simon Hock’s work, a published book, can help overcome many of these challenges. Although it is not complete, it is nevertheless possible to use the printed book as a guide to deciphering Popper’s writing. While not every entry in Popper is contained in Hock, finding the corresponding entry in the book can help make sense of what is written in the manuscript. This is made easier due to the fact that both works are alphabetized. However, searching through the Hock to find entries corresponding to those in Popper has several complications.

One of the biggest challenges I confront when searching through Hock is organization. Popper’s index is in German (except for the additional notes), while Hock is in Hebrew. Thus, although both works are sorted alphabetically according to surname, they are alphabetized using different alphabets. Not only do the letters look different, but they can come in different orders due to idiosyncrasies of transliteration. For example, the name Avner comes soon after Ausch in German, while it would be found significantly before Ausch in Hebrew (אבנר vs. אויש).

In addition to this challenge, the works’ second levels of organization are different. Within each surname (which can be 50 names or more), Popper organizes the records alphabetically by first name while Hock organizes them chronologically by date of death. [N.B.: Hock’s notebooks were originally organized alphabetically by first name, but they were rearranged into chronological order when published after his death.] Moreover, some surnames are split up in Hock – for example, people listed in Popper with the surname Altschul may be found in Hock under either Altschul or A”sh.

In spite of the many challenges of correlating Popper with Hock, the benefits are well worth it. In addition to helping me read the Popper notes, correlating the two sources allows me to include finding information (page and grave number) which will assist future database users in comparing the original sources for themselves.

Stay tuned for next time to follow the next steps in the process, and for a hint at some of the incredible things the data I am collecting can do!

Add new comment