Working on a Historic Treasure -- Prague Old Jewish Cemetery (Part 3)

My past two blog articles have dealt extensively with the Prague Jewish Cemetery. In the first one, I gave some detailed background information about the cemetery as well as the most important efforts to document it. In the second, I began to explain my process of working with these records. In this blog, I will share the rest of the process as well as some hints of the amazing things I hope to get out of these efforts.

Step 3: Standardize Surnames

One of the main points of transcribing the Popper is so that eventually people will be able to search the database for names of interest. If the same name is spelled in a variety of ways in the database, users may miss critical information, and the entire database would be harder to use. In order to make searching easier and more effective, it is necessary to use a single spelling for each surname.

On the original tombstones, surnames were written in Hebrew. These spellings are preserved in Hock, and Popper often provides them in his marginal notes. However, Popper sometimes spells the same name in several different ways in German. Moreover, any transliteration has a certain degree of ambiguity. As an example, the holiday of Hanukah can also be spelled Hannukah, Chanukah, or in any number of other ways in English.

Hebrew is a particularly difficult language to transliterate because vowels are not normally indicated. Although some consonants can imply vowels (for example, the letter hey at the end of a word implies the “-ah” sound), there is still plenty of room for ambiguity. Moreover, several consonants have multiple pronunciations. For all these reasons, a given surname spelling in Hebrew can have many possible readings in either English or German.

In order to solve this problem, I am picking a single standardized spelling for each surname I encounter. To do this, I am comparing the list of names with a list of known Jewish surnames from Prague, taken from Alexander Beider’s work (Alexander Beider, Jewish Surnames in Prague: 15th–18th Centuries, Teaneck, N.J., 1995; see: https://www.jewishgen.org/austriaczech/beiderindex.htm for the list).

Popper’s German transliterations often differ from Beider’s. In these cases, I am using the version listed in Beider. For names listed only in Hebrew in Popper, I am also using Beider’s transliterations rather than creating my own. However, finding the names in Beider is not always as straightforward as it might seem, due to the fact that the same Hebrew letter can have several different readings. Sometimes I am able to find Beider’s spelling right away, but other cases require me to manually scan through the list. In addition to standardization, using Beider can sometimes help me decipher surnames written unclearly or ambiguously in Popper.

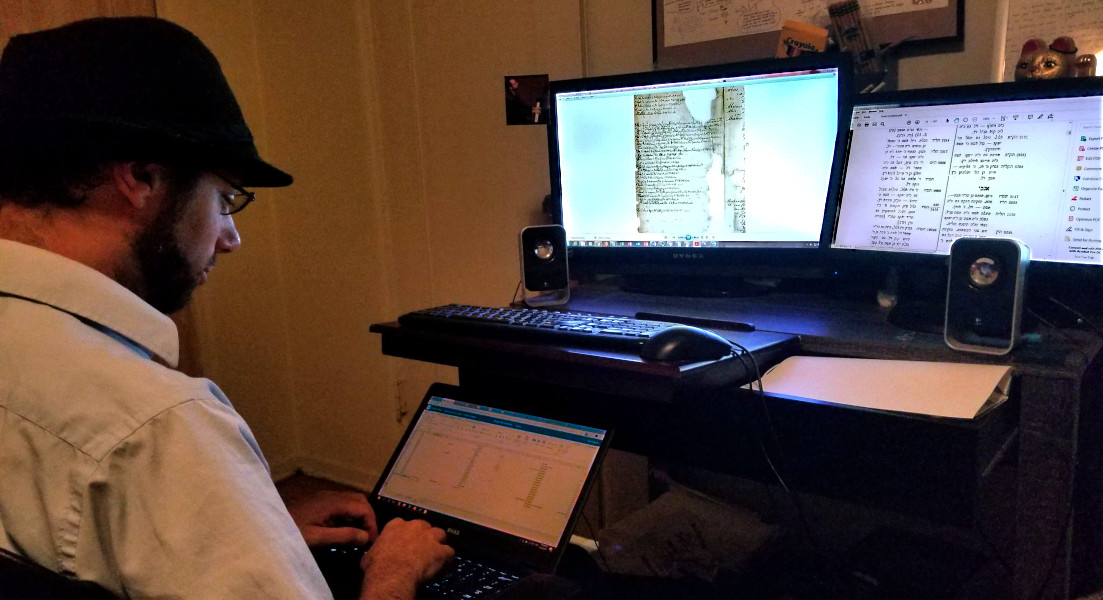

Step 4: Enter Information into the Database

Going through this information and entering it into a searchable database requires a high-tech solution. In fact, the simplest solution I could come up with requires using two separate computers simultaneously. On my desktop computer, which I have outfitted with two monitors, I place the Popper and Hock side-by-side. At the same time, I sit with my laptop computer—living up to its name—on my lap with the spreadsheet open in Microsoft Excel. This kind of work requires me to simultaneously stare at three different computer screens—in three different languages.

A Few Concrete Examples

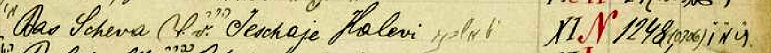

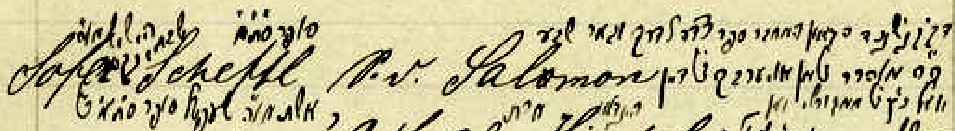

The explanations I gave may have been a bit convoluted, so let’s look at a couple of concrete examples. To start, let’s look at Bas Scheva Ashkenaz, daughter of Jeschaje, who died in 1686 (tav-mem-vav in Hebrew date notation). Here is how her record looks in Popper.

The first thing I need to do is to find her in Hock. However, the second level of organization in Hock is by date of death rather than by first name. Thus, I immediately note Bas Scheva’s death year. Instead of scanning through the Aschkenaz section by given name, I must instead scan it for the year tav-mem-vav.

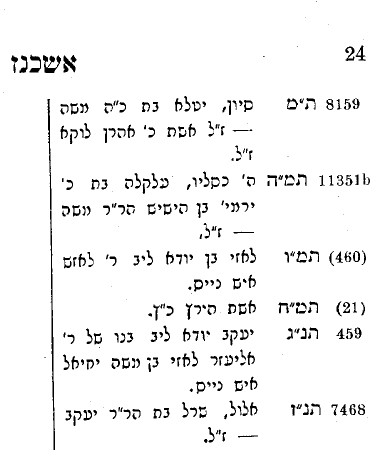

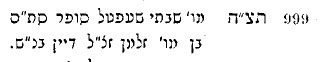

Hock’s book contains nearly fifty individuals with the surname Ashkenaz, with death dates ranging from 1604 to 1740. In the excerpt above, I show six of these with death dates of 1680, 1685, 1686, 1688, 1693, and 1696; the third one in this excerpt has the correct death year (tav-mem-vav in Hebrew notation). However, this person is a man, Lazi Ashkenaz, son of Juda. It is clearly the wrong person. Hock does not list anybody else with the surname of Ashkenaz who died in 1686.

I am not finished with Hock, however. Next, I turn to the immediate next surname, Ashkenazi—clearly a variant of Aschkenaz.

The top few lines of Hebrew are a continuation of an entry which started on the bottom of the previous column of the page (keeping in mind that Hebrew is written from right to left). The fourth complete entry in this column also has the death date of 1686 (tav-mem-vav). Reading in the Hebrew, I can see that this person’s name is Bas Sheva Ashkenazi, daughter of Yeshiah. This is clearly the correct individual.

Although today we often spell the name as “Ashkenazi,” you may have noticed that Popper spelled it “Aschkenass.” Checking in the name list taken from Beider, I see that he spells it as “Aschkenas,” with only a single s at the end. He also lists “Aschkenasi.” Using this, I enter the name as “Aschkenas” in the database with a note that the surname is written as “Aschkenasi” in Hock.

Once I have found a match between Hock and Popper, it can be very illuminating in making out Popper’s difficult handwriting. Doing so has allowed me to learn how to distinguish between different letters—particularly when Popper writes them in nonstandard ways. It can also fill in information that’s missing from Popper due to document damage.

To see what I mean, let’s look at Sofer Scheftl Auerbach, comparing how he appears in both sources. The Popper is a complete mess:

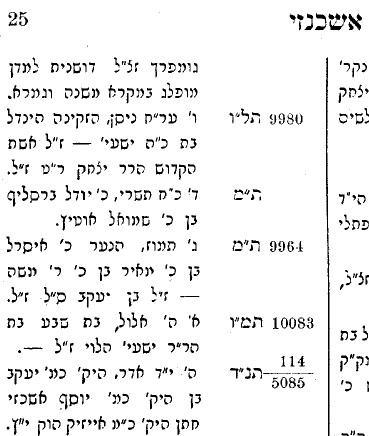

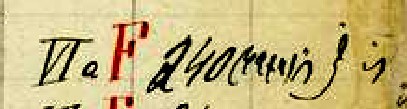

Although Sofer’s and his father’s name are easy to make out, the comments in Hebrew are tiny and almost impossible to read. Here is how he looks in the Hock:

It is immediately clear that Popper gives far more detailed information about this person than Hock. However, what Hock has to say about him has proved very useful: he was a scribe or author, and his father was a rabbinical judge [dayan]. Being made aware of this, I can recognize those words in the Popper. Moreover, I have been able to determine that much of the rest of the Hebrew notation in Popper refers to the title of his book, “The Way to Be’er Sheva” (Be’er Sheva was a biblical city in ancient Israel).

A Worthy Goal

Although this is a great amount of work, it will ultimately prove extremely valuable. First and foremost, it will greatly assist in the ability to create family trees. The main problem—and the one that this project is intended to solve—is that the existing sources give only death dates, not birth dates. For example, suppose David Aschkenasi’s record states that his father was Hersh. If there are four people named Hersh Aschkenasi, it can be very difficult to determine which one of these was David’s father.

Creating this database can help with that. In some cases, marginal notes in Popper give a general indication of the person’s age: youth, elderly, death in childbirth, etc. Very occasionally, the text will actually say how old the person was. Additionally, when naming individuals’ fathers or spouses the notes almost always specify whether they were alive or dead at the time of the person’s death. With these clues and with the aid of computerized information analysis, it should be possible to construct family trees for many of these surnames.

Moreover, meta-analysis of the data gleaned from my project should provide other fascinating insights. Popper’s marginal notes sometimes give professions, particularly religious ones such as rabbi or various synagogue officials. For people who migrated to Prague, both Popper and Hock frequently give the area of origin—often various towns in Bohemia and Moravia, but also Vienna, Amsterdam, France, Lwow, and beyond. It would be very interesting to be able to do an analysis to determine historical migration patterns. Did the places of origin of immigrants to Prague’s Jewish community change with time? If so, how? Is there any correlation between occupation and places of origin?

The answers to these and so many other fascinating questions lie hidden in these pages, just waiting to yield their secrets. Ultimately, these efforts will tell us a great deal about one of the foundational populations of Judaism in the modern world—and thus, about ourselves.

Add new comment