How to Research What Happened to Your Family in the Holocaust

One of the most common goals of Jewish genealogy research is to discover what happened to members of one’s family during the Holocaust. Unimaginable in brutality and in scope, the Holocaust affected virtually every European Jewish family. Even if your family immigrated to the United States long before the 1940s, your ancestors had relatives who stayed in Europe. Uncovering personal connections to the worst tragedy ever to befall the Jewish people can be painful, bringing up layers of buried trauma. At the same time, it can also help the process of intergenerational healing.

One of the most common goals of Jewish genealogy research is to discover what happened to members of one’s family during the Holocaust. Unimaginable in brutality and in scope, the Holocaust affected virtually every European Jewish family. Even if your family immigrated to the United States long before the 1940s, your ancestors had relatives who stayed in Europe. Uncovering personal connections to the worst tragedy ever to befall the Jewish people can be painful, bringing up layers of buried trauma. At the same time, it can also help the process of intergenerational healing.

Many people assume that Holocaust research is impossible, that all records were destroyed, or that few records were kept. However, the Holocaust is the single most documented event in human history. The Nazi perpetrators, feeling a perverse sense of pride in their crimes, meticulously documented their actions. After the war, the victorious Allied forces detailed their findings of mass atrocities, and many victims’ families have come forward with information about their loved ones. In short, uncovering what happened to your family during the Holocaust, while painful, can be fulfilling.

What Records Exist?

Contemporaneous Records

Many concentration camps kept painstakingly detailed records. Although Nazi guards destroyed much physical evidence shortly before many camps’ liberation, a surprisingly high amount survived. In the intervening time, this documentation has made its way into various government archives, Jewish institutes, and historical museums.

The types and extent of genealogical records available depends on camp type. In general, there were two distinct types of camps. Labor camps, in theory, were designed to sort arrivals and house those capable of performing forced slave labor. Contrastingly, extermination camps carried the express purpose of murdering each and every person who arrived.

For labor camps, some documentation exists for many who survived the initial selection process. In particular, many inmate transfers to other camps were recorded. Additionally, some death records for concentration camp inmates were created during periods of relatively low death rates. Contrastingly, no records were kept for people who were murdered in gas chambers or killed in other ways in extermination camps. For people who were executed immediately on being discovered rather than being sent to a camp, few if any records were created.

Many concentration camp records can be located on the Arolsen Archive website or at Yad vaShem. Additionally, the Routes to Roots Foundation maintains a Holocaust database identifying the archives in which Holocaust records are stored.

Post-Holocaust Records

Even before the end of the war, Holocaust survivors attempted to locate their missing relatives. Soon after the war’s end, the International Red Cross set up an agency called the International Tracing Service (ITS) to coordinate these efforts. Individuals seeking missing relatives submitted search request forms to the agency with the details of their family members. After searching, the agency would write back with any information it was able to obtain. Ultimately, 47 million index cards on a total of 14 million individuals were created by 1955. These cards, along with the related files, ended up in the Arolsen Archives in the town of Bad Arolsen, Germany. The Arolsen Archives have recently digitized their vast public holdings.

In the years and decades after the Holocaust, survivors sought to document and preserve the existence and historical memory of their destroyed communities. Survivors wrote books detailing everything they could remember about their cities and towns, compiling them into books called “Yizkor books.” These works are testaments to the victims and to the communities which thrived for hundreds of years before the Holocaust. Yizkor books include everything from the historical foundations of towns and their Jewish communities to World War 1 experiences to personal memories of neighbors and friends. They also include lists of names of community members, victims, and survivors. In total, more than 1500 Yizkor books have been published. Most are written in Yiddish, while some are in Hebrew; many have been partially translated into English and are searchable on JewishGen. A large collection of 645 original, untranslated Yizkor books is available digitally through the New York Public Library's Yizkor Book Project.

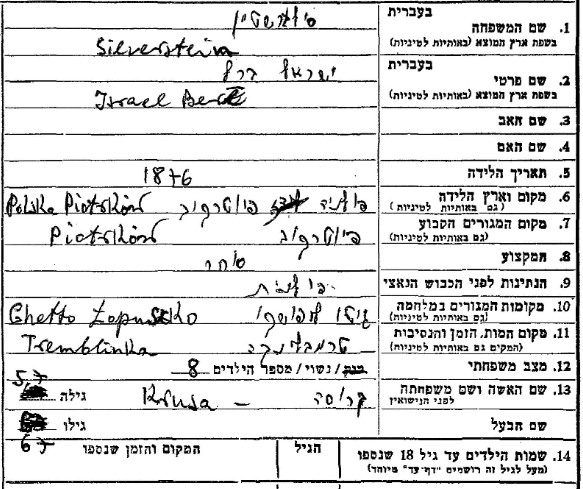

After the Holocaust, Yad vaShem was created in Israel in 1953. As the world’s primary Holocaust museum and memorial, a central part of its mission is to preserve the names of as many victims as possible. Family members were requested to submit Pages of Testimony on their relatives so that their names and fates can be preserved in perpetuity. These pages have been preserved at Yad vaShem, and the overwhelming majority have been digitized and published on the Yad vaShem website. Most pages were written and submitted in the 1950s, although pages continue to be submitted even to the present time. Many are written in Hebrew, while others are in Yiddish, Russian, French, English, or other languages. Pages include victims’ names, places of birth, places of residence before the war, occupations, family members, and places, times, and circumstances of death; some include photographs. Pages of Testimony are available on Yad vaShem’s website.

In addition to the above-mentioned sources, several other important sources of information exist. Several cities and communities have published lists of victims, and nearly comprehensive victim lists for Jews who resided within the pre-war German borders have been produced. Additionally, Jewish aid societies, including the Joint Distribution Committee, HIAS, and others, have produced records which contain valuable information on the fate of individual Jews during the Holocaust.

Challenges of Conducting Holocaust Research

As in much Jewish genealogy research, one of the primary challenges of conducting Holocaust research is language. Families dispersed widely, both before and after the Holocaust, with many families ending up in multiple countries. Some Holocaust records are written in the language of the countries the family members arrived in, others in the language the submitter was most comfortable with. Most contemporaneous Holocaust records are written in German. Consequently, researching a single family may require three, four, or even more languages.

For example, in a family that originated in eastern Poland, some members may have fled to the interior parts of the USSR after the Soviets invaded in 1939. Other family members may have perished in Auschwitz, while still others may have migrated to France, Palestine, the United States, and South America before the war. Records for this one family will likely be in Polish, German, Russian, Yiddish, French, English, Hebrew, Spanish, and Portuguese.

Most Holocaust records do not require historical handwriting—old Russian cursive was replaced with modern writing in 1917, while Kurrentschrift German was replaced with modern handwriting in 1940. However, even modern handwriting can still present a formidable challenge to modern researchers. Legibility varies greatly based on individual as well as circumstances. Moreover, reading handwriting in a foreign language places unique demands on a researcher. Finally, without context, it can be impossible to decipher handwritten names. In fact, even typed material can be challenging to work with.

Summing Up

The Holocaust was the single most devastating event in Jewish history whose memory still provokes painful intergenerational trauma to this day. We owe it to the six million victims and to the countless survivors to keep their memory alive. The many existing historical resources allow us to not only research this dark historical chapter, but to fulfill our sacred obligation to honor our families’ lives and achievements.