Surname and Town of Origin - Additional Resources

While naturalization records and passenger arrival manifests are the primary sources of information on immigrants’ places of birth and original surnames, they may not always be found. Moreover, even when they can be located, sometimes they may be missing critical information. While roadblocks (often referred to in genealogy as “brick walls”) are never fun, fortunately there are often ways around them.

Even if you were able to use them to identify your family’s town of origin, it is important to corroborate this in other sources if possible. In fact, one of the fundamental principles of genealogy research is to perform what the Board for the Certification of Genealogists terms “reasonably exhaustive research,” identifying as many pieces of evidence as possible to validate whatever data you find rather than simply accepting at face value the first piece you come across. By comparing the information found across a wide variety of sources, you are more likely to reach the most accurate possible genealogical conclusions. Thankfully, plenty of additional or alternate sources of information exist to help identify your family’s original last name and place of origin.

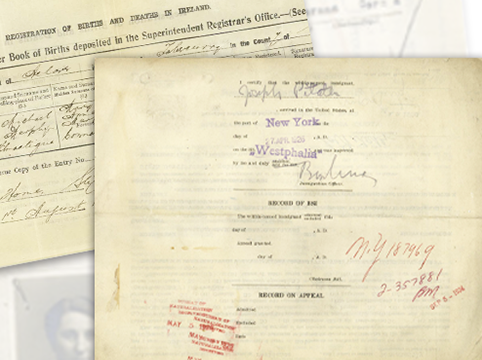

Beyond naturalization and passenger records, two additional sources of information can provide the information necessary to identify our family locations in Europe. The first, visa files, can be an invaluable source of information for immigrants who arrived in the United States after 1924. The second, military draft records for the two world wars, provide data on virtually every male resident of the United States born in the late 19th and early 20th century—including those who chose not to become citizens. For a surprisingly large number of people during this time, these two sources may be the only place to find critical information about their places of origin.

Immigrant Visa Files

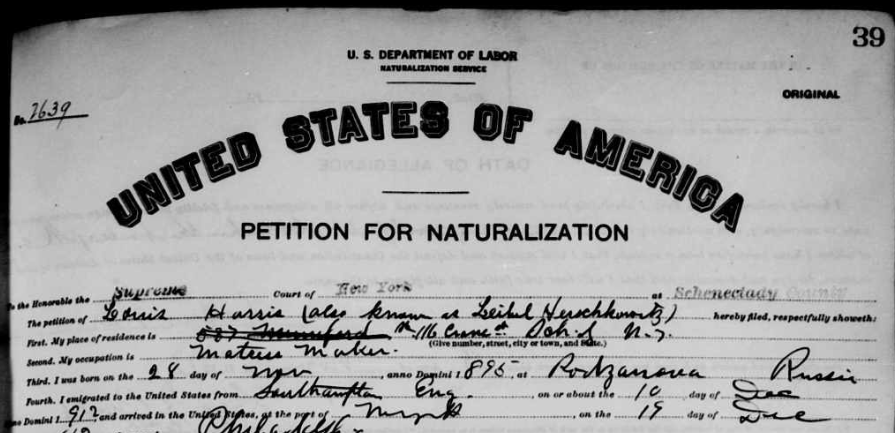

In 1924, the United States passed its now infamous quota laws, sharply limiting immigration and requiring visas for entry for the first time. As a result of these laws, all noncitizens were required to present a visa to customs agents when arriving in the United States. To receive a visa, individuals were required to submit application files with detailed information about themselves and their purpose for entering the country.

While the 1924 immigration law was harsh and discriminatory, one unanticipated positive effect is that the paperwork it generated helps facilitate present-day genealogy research. In addition to providing far more detailed information than pre-1924 records, the new visa system required information to come directly from the immigrants themselves—unlike immigration lists, which were supplied by transportation companies. Even more significantly, it was only with this quota system that immigration forms came to be considered legally binding documents whose factual accuracy is guaranteed.

Visa files typically include a large amount of information. In addition to the applicant’s complete name, a person’s visa file provides his or her birthdate, birthplace, and the names of his or her parents. Additionally, the file also typically includes a copy of the person’s birth certificate, health certification, police record, and a statement of all residences for the previous five years. Moreover, many files include marriage certificates, military records, and other assorted documents. Finally, the files almost always contain photographs of the applicants.

To obtain a visa file, use the USCIS Genealogy Program (for more information, see https://www.uscis.gov/records/genealogy/historical-record-series/visa-files-july-1-1924-march-31-1944). Unfortunately, the program has a very long wait list—as of April 2024, approximately 9 months for search results and another 9 months to receive records. If you are in a hurry, it may be better to use other sources of information if they are available. However, if you have exhausted all other avenues, obtaining your ancestor’s visa file may be the only way to determine his or her place of origin.

Using Draft Registration Cards to Identity or Corroborate Place of Origin

World War 1

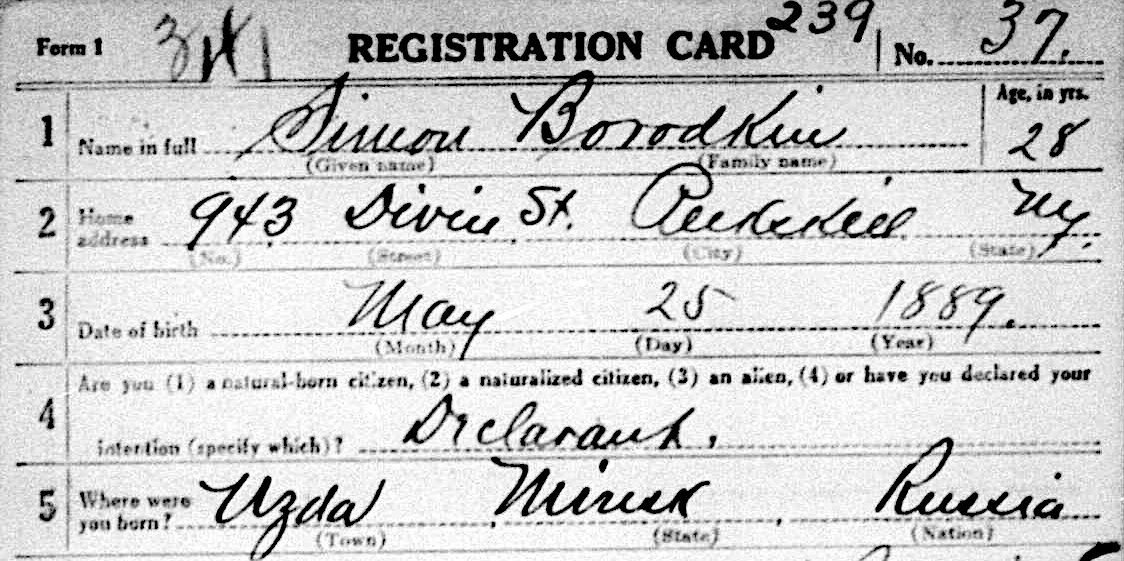

In May 1917, one month after its entry into World War 1, the United States passed the Selective Service Act. As a result of this act, all men of military age who had not volunteered to fight in the war were required to register for the draft, providing personal information to draft boards so that the government would eventually be able to call on them to serve if required. The World War 1 draft registration was carried out in three separate stages:

In May 1917, one month after its entry into World War 1, the United States passed the Selective Service Act. As a result of this act, all men of military age who had not volunteered to fight in the war were required to register for the draft, providing personal information to draft boards so that the government would eventually be able to call on them to serve if required. The World War 1 draft registration was carried out in three separate stages:

· First registration (June 5, 1917): all men aged 21-31 as of that date (births between 1885 and 1896).

· Second registration:

o June 5, 1918: men who had since turned 21 (births 1896-1897).

o August 24, 1918: men who turned 21 between June 5 and that date (births in 1897).

· Third registration (September 12, 1918): all men ages 18-45 who had not already registered in the previous two stages (births in 1872-1885, 1897-1900).

In total, World War 1 draft registrations cover the vast majority of men residing in the United States who were born between 1872 and 1900.

The registration forms for these drafts sometimes provide information which can help determine your family’s place of origin prior to immigration. Many of the registration cards asked for the individual’s birthplace. While most people in these draft records had been born in the United States, some people included in them were immigrants, so their registration cards will provide the family’s original location before they came to the United States. Even more helpfully, the second draft registration usually asked for the name and birthplace of the person’s father as well as that of the person himself. Although many of those registering only included their father’s country of birth, they sometimes specified a province, county, or even town.

World War 2

Two decades later, the United States conducted seven draft registrations shortly before, immediately following, and periodically after the American entry into World War 2. With global tensions rising and European democracies faltering, the United States instituted its first ever peacetime draft before entering the war. Registration for this peacetime draft took place in two phases:

Two decades later, the United States conducted seven draft registrations shortly before, immediately following, and periodically after the American entry into World War 2. With global tensions rising and European democracies faltering, the United States instituted its first ever peacetime draft before entering the war. Registration for this peacetime draft took place in two phases:

· September 16, 1940: men ages 21 to 45 (birth years 1894-1919).

· July 1, 1941: men who had reached the age of 21 since the first draft (birth years 1919-1920).

Five additional draft registrations followed America’s entry into the war in December 1941:

· February 16, 1942: men ages 20 to 45 who had not previously registered (birth years 1896-1922).

· April 27, 1942: men ages 45 to 64 (birth years 1877 to 1896), ineligible for military service.

· June 30, 1942: men ages 18 to 20 (birth years 1922-1924).

· late December 1942: men who had turned 18 from June 6 through November 12, 1942 (birth year 1924).

· November-December 1943: male citizens ages 18 to 45 (birth years 1898-1925) who were residing abroad.

In total, the various national drafts instituted immediately prior to and during World War 2 contain information on men born between 1877 and 1924 (also including some men living abroad born in 1925). Note that men who were born between 1877 and 1900 were required to register for both World War 1 and World War 2 drafts and will frequently appear in draft records for both wars—providing a valuable opportunity to compare information.

The information in World War 2 draft registration records is similar to those of World War 1, but tends to be more informative. In particular, World War 2 draft cards more frequently indicate place of birth. In both cases, registrants’ birthdates, residences, and names and addresses of close relatives allow modern researchers to distinguish between similarly named people and (hopefully) identify cards specifically for their families.

In short, World War 1 and 2 draft records complement the information found in ship manifests and naturalization records. They are especially helpful for locating places of origin for families who arrived in the United States and naturalized as citizens prior to the 1906 change to more genealogically useful immigration forms. Moreover, if you cannot locate your family’s naturalization records or if your ancestor never chose to naturalize, draft registration cards may be the only easily locatable source of information on your family’s place of origin.

Because the second World War 1 draft (June/August 1918) was the only one which asked for father’s place of birth, a particularly fruitful approach for families who came to the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries would be to focus first on all the men in your family who were born in 1896 or 1897 (whether in the United States or in Europe). These men will likely be included in this second draft registration, which is likely to indicate where their father was born. Next, locate the World War 1 draft cards for all the men in your family who were born prior to your family’s arrival in the United States. Lastly, identify the World War 2 draft cards for as many men in your family as you can, particularly those born before immigrating.

For even more details on the World War 2 draft, see https://www.familysearch.org/en/wiki/United_States_World_War_II_Draft_Records.

The Importance of Checking Multiple Sources

Even if the first source you check seems to provide the exact information you’re looking for, be sure to look at others as well. Because many of the sources listed above—in particular, naturalization and immigration records from prior to 1924—were not legally required to be 100% accurate, it is necessary to corroborate the information given on them whenever possible. If several documents seem to conflict, this is your signal to dig deeper. Further research may not only resolve any discrepancies, but can also help shed additional light in sometimes unexpected ways.

An example from my own genealogy practice can help illustrate what I mean. When I investigated my client Ira’s family, his grandfather Louis’s naturalization paperwork indicated a birth town of Radzanowo, which his ship manifest spelled as Radzanow (without a final vowel). Unfortunately, it turns out that Radzanow and Radzanowo are two different towns in Poland, separated by about 30 miles. Without further information, it was impossible to determine which of these was my client’s grandfather’s hometown.

On his World War 1 draft registration card, Louis indicated that he had been born in Radzanow (without the final “o”), whereas his World War 2 draft registration card gave “Mlawa.” While this seems like a completely unrelated town, further research indicated that Radzanow (without the “o”) is in Mlawa County, whereas Radzanowo (with the “o”) is in Plock County. Comparing the information in all four of these records removed ambiguity, allowing me to pinpoint which of these two very similarly spelled towns Ira’s family had come from.

Summing Up

Visa files, accessible through the USCIS Genealogy Program, are invaluable resources for locating difficult-to-find places of birth and other important genealogical details for relatives who immigrated to the United States after 1924. They are far more detailed and accurate than almost any other document you are likely to find for your family. For families who emigrated in the late nineteenth through early twentieth centuries who will not have visa files and whose naturalization and arrival documents may be unhelpful, the draft registrations for the two world wars can provide helpful clues to their places of origin.

Once you have located several sources of information on your family, you can use them to corroborate one another. Oftentimes, the information you find on one source will fill in gaps on others. Sometimes you may even be able to use this method to find surprising results—for example, distinguishing between multiple similarly (or identically) spelled towns.

But your family history did not begin immediately prior to their emigration to America. Your immigrant ancestor had parents, siblings, cousins, and extended relatives with entire histories of their own. Moreover, some of these relatives may have immigrated to other places, while others remained in Europe. Once you have used identified your family’s town of origin, you are well on your way to unlocking the secrets of your family’s story.