Finding Your Original Surname

The First Key to Ashkenazi Jewish Genealogy Research: Finding Your Original Surname

Many of my readers will no doubt be familiar with the famous story of noted Jewish immigrant Sean Fergusson. According to family lore, when arriving at Ellis Island, Fergusson was overwhelmed with the tumultuous process of arriving in America, navigating an intimidating bureaucracy in a language he didn’t speak, waiting half a day on an enormous line stretching out the door, keeping his children out of trouble, figuring out how to find a job, and a hundred other tasks. When his turn finally came and he got to the immigration window, the customs agent asked him for his name. Overwhelmed with stress, he replied, “Shayn fergessen”—Yiddish for “I already forgot.” Not understanding Yiddish, the agent wrote this down as Sean Fergusson, and a new American family of Irish-Jewish immigrants was born.

Many of my readers will no doubt be familiar with the famous story of noted Jewish immigrant Sean Fergusson. According to family lore, when arriving at Ellis Island, Fergusson was overwhelmed with the tumultuous process of arriving in America, navigating an intimidating bureaucracy in a language he didn’t speak, waiting half a day on an enormous line stretching out the door, keeping his children out of trouble, figuring out how to find a job, and a hundred other tasks. When his turn finally came and he got to the immigration window, the customs agent asked him for his name. Overwhelmed with stress, he replied, “Shayn fergessen”—Yiddish for “I already forgot.” Not understanding Yiddish, the agent wrote this down as Sean Fergusson, and a new American family of Irish-Jewish immigrants was born.

Of course, this story never happened. In fact, when immigrants arrived in the United States, their names were carefully checked off against passenger lists that had been created in Europe. The entire immigration process was thoroughly tracked from before passengers left Europe until after they arrived in America. In reality, no immigrant names were ever changed by immigration agents on arrival—in Ellis Island or anywhere else. Names being changed at Ellis Island is one of the most persistent myths in Jewish genealogy.

While names were never changed by immigration agents, it was very common for Jewish immigrants themselves to eventually “Americanize” their last names after they had already settled in the United States. Therefore, if your family’s surname is not a “typical” Jewish name, it may have been changed by one of your ancestors. Without knowing what your family’s original surname was, it will be impossible to find any information about them before they came to America. Learning your family’s original surname presents a significant challenge—yet is one of the two critical pieces of information you will need to be able to unlock your family’s deep past.

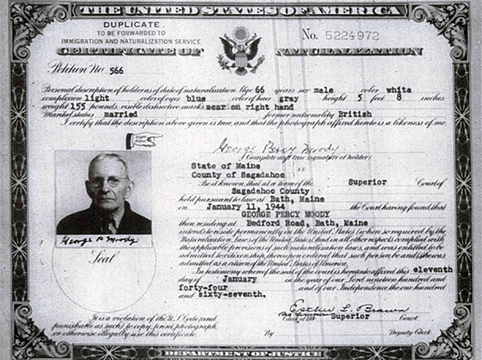

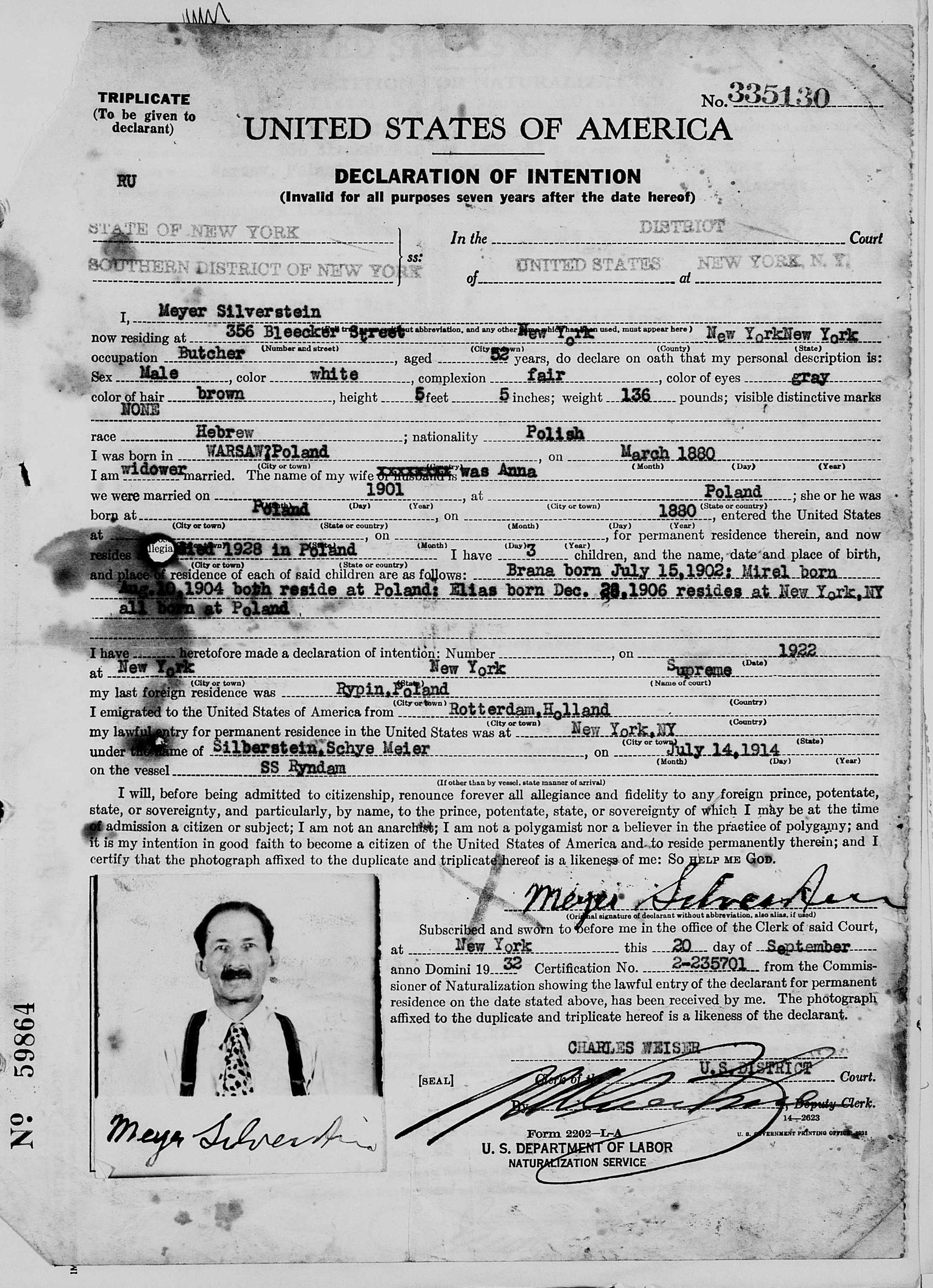

Fortunately, information is available to help you identify your family’s original surname. The best place to start is naturalization records. Among much other useful information, naturalization records frequently make the connection between immigrants’ old and new names. Moreover, they usually provide certificates of arrival, which definitively prove the linkage between the two. However, if your ancestor’s naturalization record does not provide an original surname, or if you cannot find a naturalization record, alternate procedures exist which may allow you to make an educated guess as to your family’s pre-emigration surname.

Using Naturalization Records to Find Your Ancestors’ Original Surnames

Once they arrived in the United States and settled into their new lives, many immigrants chose to become citizens. Immigrants wishing to make this choice were required to fill out paperwork and file it with the government. They chose to do so for a variety of reasons, ranging from economic pressure to a desire to fit in to proud American patriotism.

Naturalization was a multi-step process which generated several rounds of paperwork. The first stage of the process was called the declaration of intention. Also known as “first papers,” this document formally notified the United States government of his or her intent to eventually become a citizen. Once the immigrant qualified for naturalization (typically after five years), he or she would be allowed to file a petition for naturalization (also known as “final papers”). If the applicant’s petition was accepted, he or she would receive a court order, a certificate of arrival (for naturalizations in or after 1906), and a certificate of naturalization.

Unfortunately, early naturalization records provided little useful genealogical information. However, a new federal immigration law took effect on September 29, 1906 which affected naturalization forms. For immigrants who naturalized after that date, naturalization files provide many useful details, including original given name and surname, adopted given name and surname (if any), birthplace, arrival records, place of residence in the United States, the names and birthdates of spouse and children. However, information provided by the immigrant was not required by law to be accurate. For this reason, think of the information you find on naturalization records as a clue for further research rather than as a definitive answer.

Additionally, not everyone who became citizens was required to file paperwork. In the United States, children under age 21 have always been naturalized through their parents (although some minors were allowed to naturalize separately from their parents between 1824 and 1906). Also, in cases where both spouses were aliens, wives naturalized automatically through their husbands between 1855 and 1922, while alien women automatically became U.S. citizens by marrying American husbands. Therefore, if your family immigrated during that time, it is unlikely that you will find naturalization papers for your ancestor’s wife or children.

How to Find Naturalization Records

While many naturalization records are available via Family Search or in commercial genealogical programs, not all are. If you are unable to find a naturalization record using sites like Family Search or Ancestry.com, you may need to perform a manual search. To locate your ancestor’s naturalization papers this way, you will need to know which court he or she naturalized in as well as the approximate date of naturalization. Moreover, this information will also help distinguish between the naturalizations of different people with the same first and last names as your immigrant ancestor.

The information can be found, or at least approximated, in several sources. First, most census records state whether a person was a naturalized citizen or an alien, allowing you to easily tell if a person naturalized between two censuses. More helpfully, the 1920 US federal census gives the approximate year of naturalization, while the 1925 New York State census provides the approximate year and location of naturalization. In addition to census records, voter registration records often provide the date and location of naturalization. Finally, US passport applications may also provide it.

Once you have identified your ancestor’s naturalization date and court, the process of obtaining a copy of the paperwork depends on where and when the naturalization occurred.

Finding Pre-1906 Naturalizations

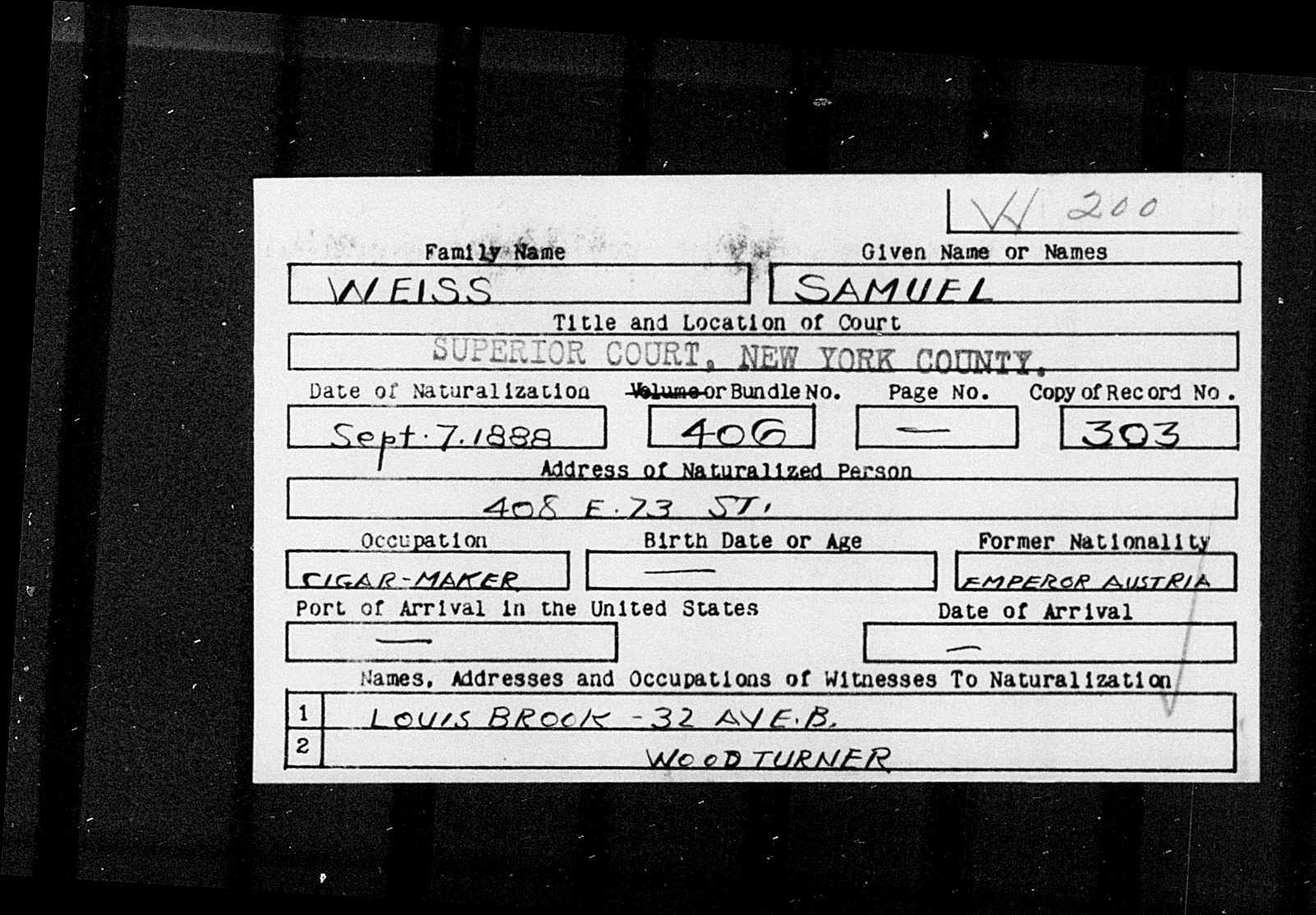

For naturalizations prior to 1906, naturalization forms typically contain very little useful information, so your time is probably better spent looking for other sources. However, if you can’t find the information elsewhere, or if you hope to corroborate information in other records, finding pre-1906 naturalizations can be quite challenging.

Before 1906, immigrants could naturalize in virtually any court, including federal, state, county, city, police, or civil courts. It may be extremely difficult to determine which court your ancestor naturalized in. Fortunately, there are comprehensive indexes for people who naturalized prior to 1906 in the New England states (https://www.familysearch.org/search/collection/1840474), in most New York City courts (https://www.familysearch.org/search/collection/2043782), and in greater Chicago and certain other areas of the Midwest.

If you are able to determine which court your ancestor naturalized in, you will likely need to perform additional research to locate the paperwork. To the extent that records of these early naturalizations still exists, they may be stored in local courts, government archives (national, state, or local), warehouses, or private collections. No nationwide central repository of these naturalization records exists. All records for naturalizations that occurred in federal courts (either before or after 1906) are stored in the National Archives. However, you will need to determine how to locate naturalization records for non-federal courts.

Finding Post-1906 Naturalizations

After 1906, immigrants were no longer permitted to naturalize in police, civil, or other small courts, or in most city courts. Some city courts were allowed to continue issuing naturalizations, but most people naturalized in federal, state, or county courts. Fortunately, unlike pre-1906 naturalizations, finding naturalization records from after 1906 is relatively straightforward.

Between 1906 and 1992, three copies of naturalization papers were issued. The first copy was given to the person who naturalized, while a second copy was retained by the court that issued it. A third copy of the naturalization forms was sent to the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS, the precursor to today’s USCIS), no matter where the immigrant chose to naturalize. Fortunately, both the INS and court copies of naturalization papers are usually accessible to modern researchers.

INS copies of naturalization records can be obtained by contacting USCIS. Between 1906 and 1956, the INS copies were stored in a centralized repository, in the so-called “C-Files” (Certificate Files) system. After 1956, the INS naturalization paperwork was housed in various locations scattered throughout the country. Rather than in the C-Files system, post-1956 naturalization papers are stored in A-Files (Alien Files); each file in the A-File system refers to a specific person.

To access naturalization papers in either the C-File or A-File system, write to USCIS. A Freedom of Information request may help expedite access to C-File records, while it is usually mandatory for accessing A-File records. For more detail on how to obtain copies of naturalization records from USCIS, see https://www.uscis.gov/about-us/our-history/history-office-and-library/research-guides/researching-individuals.

Unfortunately, obtaining records from USCIS may take months or longer. Moreover, the scans you receive from them may be of questionable visual quality and exceedingly difficult to read—particularly for pre-1956 records. What you receive from USCIS may be digital copies of 70-year-old microfilm. Therefore, obtaining the INS copies of naturalization records may not be the best way to obtain your family’s naturalization records.

If you are able to determine which court your ancestor naturalized in, it will probably be much faster to obtain the copies of naturalization records retained by that court. Moreover, the images you receive will probably be of significantly better visual quality than what USCIS would provide. If your ancestor filed for naturalization in any federal court prior to October 1991 (whether before or after 1906), the records will be housed in a regional branch of the National Archives. Contrastingly, post-1906 naturalizations which were originally filed in state, county, or city courts will most likely be located in state archives. Discovering exactly where to locate non-federal post-1906 naturalizations will take a bit of research on your part, but will be significantly easier than locating pre-1906 ones.

Summing Up

Originally created to enforce federal immigration law, naturalization records provide modern researchers with a valuable window into our ancestors’ lives. While the information contained on them varied over time, they are one of the best tools for furthering our genealogy research. For Ashkenazi Jewish families, naturalization records typically provide the best way to find our family’s original names. Moreover, they also provide a stepping stone to the second step of our research, identifying our Ashkenazi Jewish family’s location of origin.

Occasionally, however, naturalization records cannot be found. In other cases, they might not contain enough useful information to allow us to identify our family’s original surname. In these cases, alternate genealogy methods can be used to further research.

In either case, we are well on our way to unlocking the secrets of our family’s stories.