Historical Handwriting for Ashkenazi Jewish Genealogy

As previously discussed, the backbone of genealogy research is utilizing primary source records, comparing them against one another to form sound conclusions. Many of these historical documents are handwritten, and the ability to read them can be paramount for reconstructing the histories of our families. For genealogists, the ability to read cursive writing is indispensable, yet it often comes with significant additional complications.

While reading handwriting in our native language is quite straightforward, as genealogists we are often confronted with handwritten documents in our ancestors’ native languages rather than our own. At the same time, languages including German, Russian, and Hebrew—critical to Jewish genealogy research—were written entirely differently in the nineteenth century than they are today. This can present extreme challenges, but can also provide exciting rewards—as in my own professional and personal research.

The Challenges of Foreign Handwriting

Reading handwritten material in a foreign language takes special skills. To see this, think for a minute about reading handwriting in your native language. Each person’s handwriting is unique, with some people’s writing more legible than others. When you read a handwritten document that was drafted by someone with messy handwriting, it can sometimes be challenging to figure out. However, since you’re already familiar with the words in your own language, you often already know what word to expect when you get to a word you can’t read. If you are unsure of what a poorly written word says, it is usually possible to guess at it from the context.

Conversely, reading printed material in a foreign language is also relatively easy. When you encounter a word you don’t understand, you can look it up in a dictionary to determine its meaning. While this requires an understanding of how words change given the grammatical peculiarities of whichever language you’re reading in, it is still a relatively straightforward process.

In contrast to these two situations, reading handwritten material in a foreign language can be very challenging. When you see a word you can’t read, you probably will not know what word to expect. In cases like this, it is much more difficult to figure out what word to look up in the dictionary. For handwritten writing, reading and comprehension are parts of the same act. For this reason, brushing up on your knowledge of relevant languages—perhaps taking a semester or two of German or Russian at a local community college—will be exceedingly helpful for your genealogy research.

The ability to read handwritten material in any foreign language takes a lot of patience, trial, and error. Yet some languages present far greater obstacles.

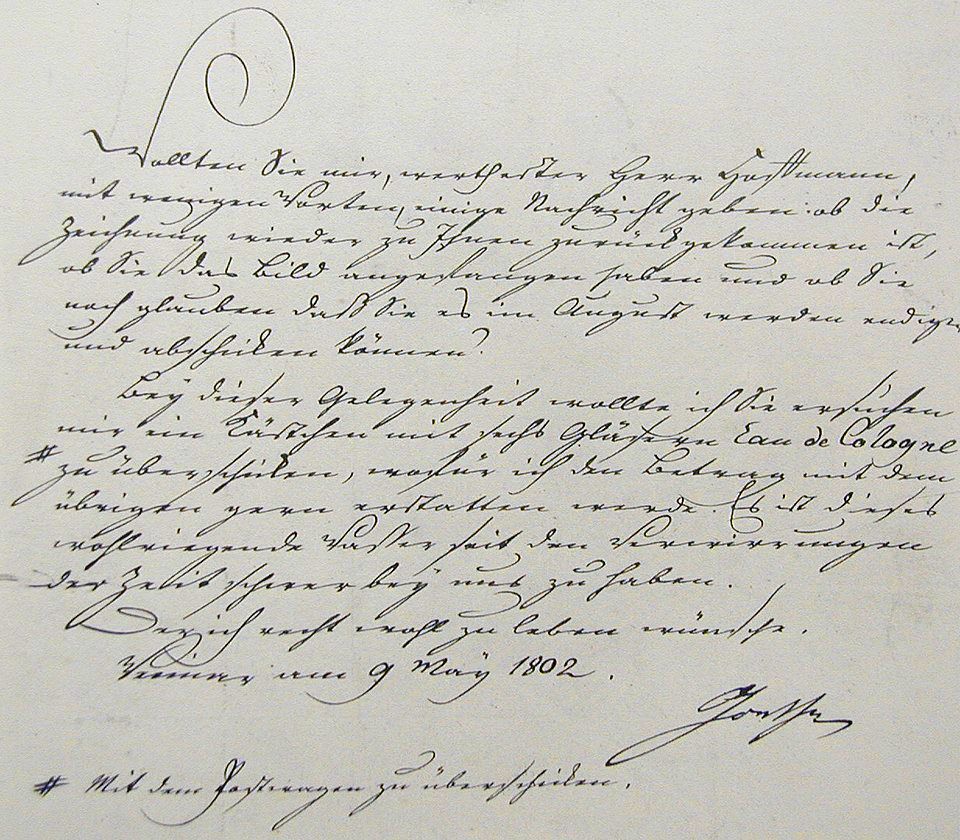

German Historical Handwriting (Kurrentschrift)

Today’s German is written in letters virtually identical to English—both in print and cursive. Although there are a few exceptions such as ö or ß, most German letters are exactly the same as English ones. However, German was written very differently prior to 1940. While it did use the same alphabet—unlike Hebrew, Arabic, or Russian—its letters had very different forms than what we are now used to. This type of writing is known as “Kurrentschrift”; between approximately 1910 and 1940 it was called “Sütterlin” or “Sütterlinschrift.”

Not in official use since 1940 and not taught in German schools since the 1970s, the ability to read it is rapidly disappearing. The differences between Kurrentschrift and modern German handwriting are so profound that it is difficult or impossible to read it without special training, even for native German speakers. In fact, in recent years it has become an increasingly serious problem to find German postmen who can deliver mail addressed by the older generation.

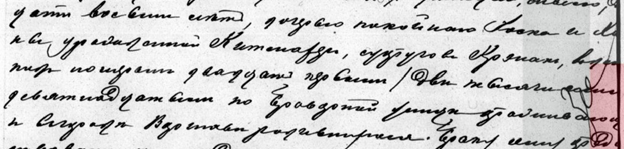

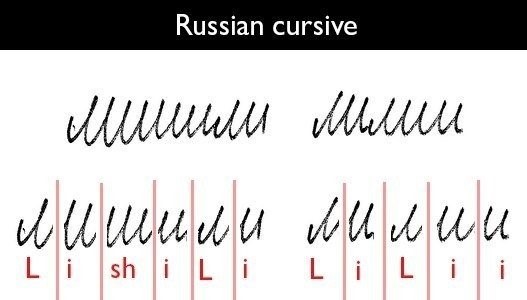

Russian Cursive Handwriting – Historic and Modern

Like English and German, Russian includes a handwritten version of its alphabet. In general, Russian cursive presents many challenges. To see this, consider English cursive for a moment. If a person does not write carefully, a cursive “e” can look like an “l” or a “c,” “o” can look like “a,” and the letter combination “cl” can look like a capital “I.” Several other letters can also be easily mistaken for one another. However, when written carefully enough, everything is distinct.

Like English and German, Russian includes a handwritten version of its alphabet. In general, Russian cursive presents many challenges. To see this, consider English cursive for a moment. If a person does not write carefully, a cursive “e” can look like an “l” or a “c,” “o” can look like “a,” and the letter combination “cl” can look like a capital “I.” Several other letters can also be easily mistaken for one another. However, when written carefully enough, everything is distinct.

As in English, some cursive Russian letters can look extremely similar to one another and are easily confused. However, in contrast to English cursive, several Russian cursive letters or letter combinations are written identically to others even if one writes absolutely perfectly. In fact, sometimes entire words look identical to completely different words; readers can only distinguish these via context. Moreover, the angularity of Russian cursive can sometimes present significantly greater challenges than English, even to native Russian speakers.

To make matters worse, old Russian writing is significantly different from modern Russian. In 1917 there was a spelling reform in the Russian language, eliminating several extraneous letters from the alphabet. Moreover, the hard sign (“ъ”) was eliminated from the ends of most words. Although the letter was retained for certain situations, it became relatively rare. Even more, several other letters had multiple handwritten forms which are no longer encountered in modern Russian cursive. Compounded with the variability of individual handwritings, pre-1917 Russian cursive writing is quite challenging to the modern researcher.

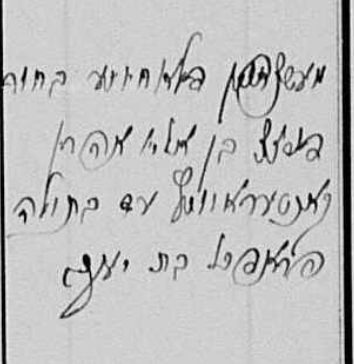

Reading Hebrew and Yiddish

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, most genealogy records were written in the official languages of the countries where they were located. Thus, a perhaps surprising amount of knowledge can be gained about Jewish families without any knowledge of Hebrew. However, Hebrew does play an important role in Jewish genealogy.

In the Russian Pale of Settlement, many vital records were written bilingually in Russian and Hebrew. It can be quite useful to be able to check one version against the other to verify comprehension and to overcome poor scribal penmanship. Moreover, any differences between the two can be particularly revealing. Other documents, both in Russia and in other places, may be written only in Hebrew. Such documents typically include tombstones, published books, older documents, ketubbas (religious marriage documents), and other special sources. Thus, knowledge of Hebrew can be extremely helpful in extending research beyond the standard sources.

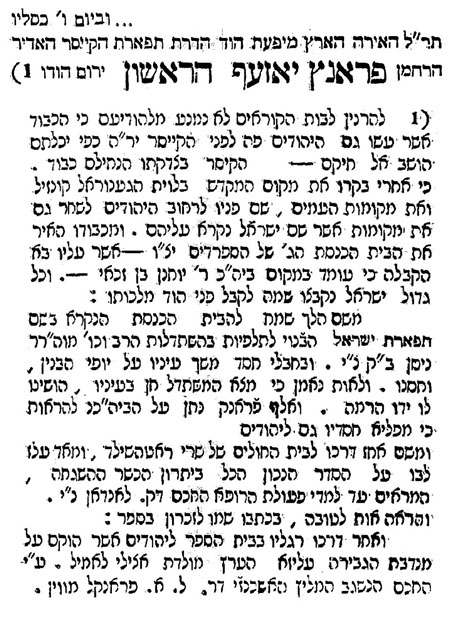

Pre-20th century Hebrew cursive is similar to modern cursive, but still presents challenges. In historical Hebrew-language handwritten documents, letters can vary widely in size, spelling can fluctuate wildly, and spaces between words are frequently eliminated. Moreover, writers often add ornamental flourishes, and some of the letters can look a bit different to what we are used to—alef’s can look like two vertical lines or two vav’s, lamed’s can look like long vertical lines, and he’s can end up looking something like rainbows. Finally, 19th-century cursive Hebrew letters are often joined together, whereas in modern Hebrew cursive they never are. As with all forms of Hebrew, vowels are almost never indicated.

In addition to print and cursive, an additional form of Hebrew writing also exists. Although it is frequently called “Rashi script,” it is not actually a script but rather a typeface, as it is used for printed material rather than handwriting. Traditionally, it was used for Biblical commentary as a way of differentiating later additions from the original text. It was most famously for the works of medieval French scholar Rashi (Rabbi Shlomo Yitzchaki, 1040-1105), hence the name.

In the nineteenth century, Rashi type was often used in printed Hebrew material, both religious and secular. In many Hebrew-language books and newspapers, this typeface serves a similar function as italics in English. However, it is often used for whole paragraphs or sections at a time rather than for individual words.

Learning to Read Foreign Historic Scripts

A variety of resources are available to learn these alphabets and scripts. Family Search has an online tutorial for German (https://www.familysearch.org/en/help/helpcenter/lessons/old-german-script-part-1), although its tutorial for Russian (https://www.familysearch.org/help/helpcenter/lesson/76) seems to have been taken offline.

The best approach may be the simplest one. Using German, Russian, or Hebrew alphabet charts, simply go through historical materials one letter at a time. Using your knowledge of the language to guide you, compare each letter in the document to a letter on the chart. With a bit of practice, you will soon be able to recognize frequent letter combinations (such as “sch” or “pf” in German), syllables, and complete words. Eventually, you will be able to read historical documents with ease.

Summing Up

The ability to read original records is invaluable in genealogy research. Original records often provide important details that may be left out of indexes and databases. Moreover, many documents are not covered in databases; being able to read and understand them can drastically add to our knowledge of our families’ histories. For many important reasons, using primary rather than secondary sources is one of the fundamental principles of the genealogy professional standards and ensures the most accurate possible research conclusions.

Although it will take a lot of tenacity, learning to read old German, Russian, and Hebrew handwriting will have a drastic impact on your ability to research Ashkenazi Jewish families. By uncovering the secrets held within old handwritten documents, you can solidify your research, bring your family’s story to life, and preserve the memory of those who came before you.