Researching Jewish Families in Prussian Poland

While resources for Jewish genealogy in Galicia and Congress Poland are relatively well known, those for Prussian Poland are perhaps less familiar. However, a wealth of genealogical sources awaits the tenacious researcher with family origins in this somewhat neglected region.

What Is Prussian Poland?

As described in my page about Jewish history in Poland, Prussia took control of Polish territory during each of the partitions of Poland in 1772, 1793, and 1795. While Jews had lived in Prussia long before 1772, the German state gained a large Jewish population with the incorporation of formerly Polish territories (as did Austria and Russia).

In 1807, Napoleon created a new political entity called the Duchy of Warsaw out of much of the Polish territory Prussia had gained over the preceding decades. As a reward to the King of Saxony for his alliance with Revolutionary France, Napoleon granted it to Saxony as a protectorate. Following the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, the Congress of Vienna attempted to restore the political status of Europe to what it had been before the conflict while punishing France and its former allies.

As a result of the Congress of Vienna, large portions of the Duchy of Warsaw became Congress Poland. However, the westernmost portion was returned to Prussian control as the newly created Grand Duchy of Posen. At first, Posen retained nominal independence as a Prussian protectorate; however, it became fully incorporated into Prussia as its seventeenth province in 1850. Of Prussia’s former Polish lands, Posen had the highest concentration of Jews.

In addition to Posen, Prussia also maintained additional territory taken from Poland during the Partitions. These areas, located north and west of Posen, had remained a part of Prussia throughout the Napoleonic and post-Napoleonic period. During the nineteenth century they were annexed to the Prussian province of West Prussia.

Under the leadership of Otto von Bismarck, Prussia was the primary force in the establishment of the German Empire in 1871. As a result of the unification of what had previously been a multitude of nominally independent states, economic conditions improved and personal mobility increased. Seeking greater opportunities in places like Berlin, Breslau (now Wrocław, Poland), Munich, and other major German cities, the overwhelming majority of Jews in Posen and West Prussia migrated to other parts of the country during the mid-nineteenth to early twentieth century.

By the 1920s, the Jewish population of Posen and West Prussia was only 5% of what it had been in the early nineteenth century. As a result, few American Jews will have ancestry directly from here. Instead, it will be much more common for Jews researching their family backgrounds in other parts of Germany to discover that they have more distant origins in Prussian Poland.

What Information is Available for Prussian Poland?

Vital Records

Like most states in nineteenth-century Europe, Prussia kept birth, marriage, and death records beginning in the early to mid-nineteenth century. These records form the backbone of genealogy research, whether for Jewish genealogy or for that of any other group. Many nineteenth-century Prussian vital records have survived and are housed in German archives; they can also be researched via Family Search. In addition to vital records, several other important documents exist.

Surname Adoption Lists

Jews in Prussia took surnames in four stages. The first Prussian Jewish to receive family names were those in Silesia in 1790. Several years later, Jews in certain areas of Prussian Poland were required to take last names in 1797. In 1812, Jewish surnames were granted in areas that had been part of Prussia prior to the Polish partitions, except for the areas where this had already been done in 1790. Finally, in 1833 Jews in Posen were allowed to take family names. Although the 1833 law theoretically only applied to those who could prove their eligibility for citizenship, this restriction was not widely enforced.

Surname adoption lists for 1812 (Prussia) and 1833 (Posen) have survived and are held by FamilySearch; they are also available in the Jewish Historical Institute in Warsaw and the Deutsche Zentralstelle in Leipzig. These documents specify the names of individuals before and after taking on last names. Because Jews were traditionally identified by given name and patronymic, these lists allow researchers to trace their family back an additional generation.

Police Records

Polish district state archives often contain local police records for villages and towns. For Prussian Poland, these records may be surprisingly valuable for Jewish genealogy. In much of Europe, poor Jews frequently worked as peddlers, a profession which was technically illegal in Prussia beginning in 1797. As a result, poorer Prussian Jews in the nineteenth century were far more likely than wealthier ones to have criminal records. At the same time, it was much more common for wealthy Jews to have their births, marriages, and deaths officially registered. Therefore, information found in police and criminal records largely complements vital records for Jewish families in this region.

Other Records

In addition to surname adoption lists and police records, numerous other record collections are available which shed light on Jews in Prussian Poland:

· Tax records

· Land records

· Censuses

· Business, address, and telephone directories

· A large collection of pinkassim (Jewish community records intended for internal use by the community), held in the Gottesman Library Rare Book Room at Yeshiva University in New York.

· 1895 school yearbook for the Royal Catholic High School in Ostrowo. Although a Catholic school, many Jews attended. Some of its graduates became rabbis, while others emigrated to the United States.

Where to Find Jewish Records for Prussian Poland

Databases

In addition to JRI-Poland and Family Search, another extremely useful database is Familiendatenbank Juden im Deutschen Reich (Jews in the German Empire) (https://ofb.genealogy.net/juden_nw/). Spanning the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the database covers hundreds of thousands of Jewish individuals who lived within the pre-WW1 boundaries of the German Empire.

Polish Archives

Records which are not available online will generally be available through either the German or Polish archives. For Polish archives, records over 100 years old will usually be located in state archives—although those contained in books which also include more recent records will not be transferred until the youngest records they contain turn 100. Records less than 100 years old are housed in local town archives (USC) rather than state archives. To access these records, one generally is required to show proof of blood relationship to the named person, or to show a death certificate.

Similar to pre-1826 Congress Poland, Jewish vital records in Prussian Poland may be found in Catholic church registers. However, unlike the case with Congress Poland, in some towns too small to have an official Jewish community, Jewish records were maintained by the local Catholic church not only until 1826 but even as late as the 1870s. Some of these Catholic registers may still be in the possession of the Church.

If pre-1874 Jewish records do not seem to exist for the town you are searching for, locating them requires a specific procedure. First, check the backs of Catholic record books for that town. If you do not find any Jewish records there, check those of the nearest larger town. If nothing turns up there either, check the local Catholic diocesan archive.

During the Communist period, some church records were relinquished to government control. After 1989, the government was supposed to return them to the Church. However, it did not always do so. Therefore, if no records at all (Christian or otherwise) turn up for a diocesan archive which you suspect may hold Jewish records, check the district archive.

German Archives

In addition to state archives, several important private archives for Jewish genealogy exist in Germany. First, the Stiftung Neue Synagoge Berlin-Centrum Judaicum (https://centrumjudaicum.de/historisches-archiv) has a detailed index and many files from the Gesamtarchiv der deutschen Juden, c.1750-1931. Although not actually complete (despite the title), the index is still extremely useful. Arranged by town, the archive holds a large collection of records documenting the Jewish German community, particularly that of Prussia. Unfortunately, this archive is temporarily closed to visitors pending building maintenance. Secondly, the Deutsche Zentralstelle für Genealogie in Leipzig (https://www.staatsarchiv.sachsen.de/index.html) holds a vast collection of records of Jewish interest.

Outside of Berlin and Leipzig, the Frankfurt Jewish Museum’s Brilling Archives (https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn522418) also hold important documents to the Jewish community from former Polish areas of Prussia. Originally the private archive of renowned genealogist and rabbi Bernhard Brilling (1906-1987), they were donated to the Frankfurt Jewish Museum by his widow. Among the myriad of documents are items such as historic photographs, Prussian Jewish naturalizations, and census extracts containing names and ages of heads of household family size, length of residence, and location of children not living with parents. The Brilling Archives have been housed at the United States Holocaust Museum and Memorial since 2004.

Unique Issues for Researching Prussian Poland

One of the major issues in researching Prussian Poland is locating the records. By international archival convention, archival records are supposed to be kept in countries in which the territories they cover are currently located. Consequently, records for towns which at one point were in Germany but were transferred to Poland after World War 2 are supposed to be housed in archives in Poland. Following this convention, East Germany transferred large sets of records to the Polish Archives during the postwar era. However, this procedure was not universally followed. As a result, a significant number of records for towns currently in Poland are still located in German archives. In addition, many records that were once housed in Germany have since been scattered to a variety of private archives around the world. For this reason, locating records for your town of interest may be challenging.

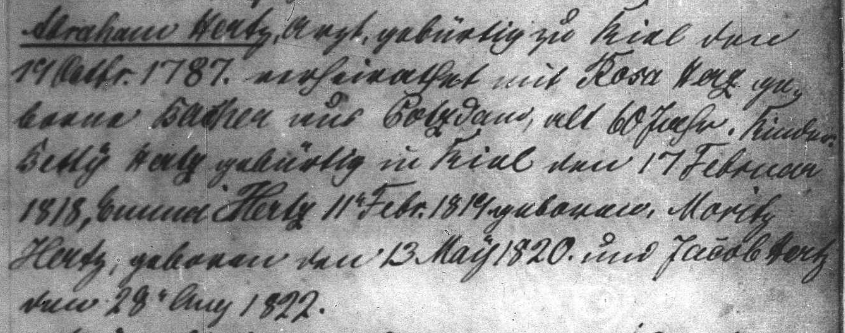

In addition to locating records, an additional major challenge in researching Jewish families from Prussian Poland is handwriting. As with Galicia, Prussian Polish research requires reading German handwriting which prior to 1940 was written entirely differently. Reading old German handwriting requires specialized training to read—even for native German speakers.. Moreover, as with any genealogical research, handwriting quality and scan legibility vary widely.

Summing Up

Since most Jewish families from Prussian Poland migrated to other areas in Germany in the late nineteenth century, the region does not play an oversized role in the immediate histories of most German Jewish families. However, the area was an important one, with significant numbers of families having more distant origins there. If research on your family ultimately leads you here, the myriad of genealogy records which exist for this region can shed a great deal of light on your genealogy—despite the many challenges inherent to using them.