Researching Jewish Families from Lithuania

If your family came from Lithuania, you may think that all records of it were destroyed during the Holocaust. However, this is one of the most common misconceptions in Jewish genealogy. In fact, millions of Jewish genealogical records spanning hundreds of years are preserved in archives both inside and outside of Lithuania.

Genealogy research for Lithuanian families is challenging but can be vastly rewarding. While many researchers struggle with the language barrier, persistence pays off. If you are prepared to deal with a profusion of databases, international archives, and pre-1917 Russian and Hebrew cursive handwriting, the history of your family lies waiting to be uncovered.

Historic Foundations of Lithuania

Founded in the thirteenth century on a territory rather similar to its current boundaries, the Duchy of Lithuania, the medieval forerunner to the modern country, expanded greatly during the Middle Ages. By the fourteenth century Lithuania became one of Europe’s largest countries, encompassing all modern Belarus along with much of today’s Ukraine. At its greatest territorial extent, Lithuania spanned from the Baltic to the Black Sea. The country became even larger in 1529, when the Treaty of Lublin formally unified it with the Kingdom of Poland to form the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, a union which existed for two and a half centuries. In the 1790s, the lands of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth were split among Austria, Prussia, and Russia, with nearly all former Lithuanian lands going to Russia.

Lithuania remained part of the Russian Empire from 1795 until its 1917 disintegration. During the interwar period, the country became independent again, although Vilnius, its historical capital and largest city, came under Polish control as a result of the Polish-Lithuanian War of 1920. Lithuania was invaded by the USSR in 1940, then by Nazi Germany in the following year. On their march to Berlin, the Soviets forcefully integrated the country back into the Soviet Union, creating the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic. Lithuania has been an independent nation once again since the collapse of the USSR in 1991.

History of Jews in Lithuania

Jews have lived in Lithuania since the 12th century; as the last country in Europe to be formally converted to Christianity, Lithuania tended to promote greater religious tolerance than many other countries in the region. The earliest Jewish populations of Lithuania came from three main sources. The first group of Lithuanian Jews were the descendants of traders who had migrated northward from southeastern Europe. Later in the Middle Ages, the Jewish population of Lithuania expanded due to migration from western Europe as Jews fled crusades in the thirteenth century and persecution in the wake of the fourteenth-century Black Death epidemic. A century later, when Lithuania expanded its territory to the southeast in the fourteenth century it acquired new Jewish populations who had already resided in those lands.

As in many other areas, most early Jewish settlers in Lithuania were traders and merchants who sold to agrarian local populations. Similar to the situation in Poland, Jews in Lithuania came to function as intermediaries between the resident peasantry and the aristocratic landed gentry. As a result of their economic position which tended to concentrate Jews in urbanized areas, many towns in early modern Lithuania came to have Jewish majorities.

In the seventeenth and eighteenth century, a golden age of Lithuanian Jewry flowered. Rebuilding from the ashes of the Khmelnitsky Uprisings which decimated Jewish communities in the southern part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (current-day Ukraine) and invasions by both Russian and Swedish armies in the north, Jews reestablished their communities in Lithuania as places of learning. Elite yeshivas proliferated, transforming Lithuania into a world-renowned center of Jewish life and the study of Torah.

The nineteenth century saw a huge growth of the Jewish population in Lithuania, as well as a surge in emigration. The Industrial Revolution, which began to reach the region by the 1850s, sparked a mass migration of both Jews and non-Jews to burgeoning nearby cities in eastern Poland as well as further afield to Warsaw, Odessa, and Latvia. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, many Lithuanian Jews immigrated to the United States, the UK, and South Africa (the majority of whose Jewish population has Lithuanian roots). At the same time, many of the Jews who remained in Lithuania were proudly patriotic, with significant numbers volunteering to serve in the Lithuanian army during its war of independence.

Approximately 94% of Lithuanian Jews who had not emigrated were killed during the Holocaust, both by Nazis and by their local collaborators. Lithuania suffered one of the highest percentages of Jewish deaths in all Europe. Several hundred Jews managed to survive the ghettos in Vilna (Vilnius), Kovno (Kaunas), Siauliai, Suwalki, and a few smaller locations, while other Jews fled to the interior of the Soviet Union.

Although much of the remaining Jewish population left during the late Soviet period, in independent Lithuania a small Jewish but thriving community of several thousand individuals remains. According to official government statistics published in 2021 by the National Minority Department, Jews currently form the fifth-largest minority group in Lithuania.

What Records Are Available?

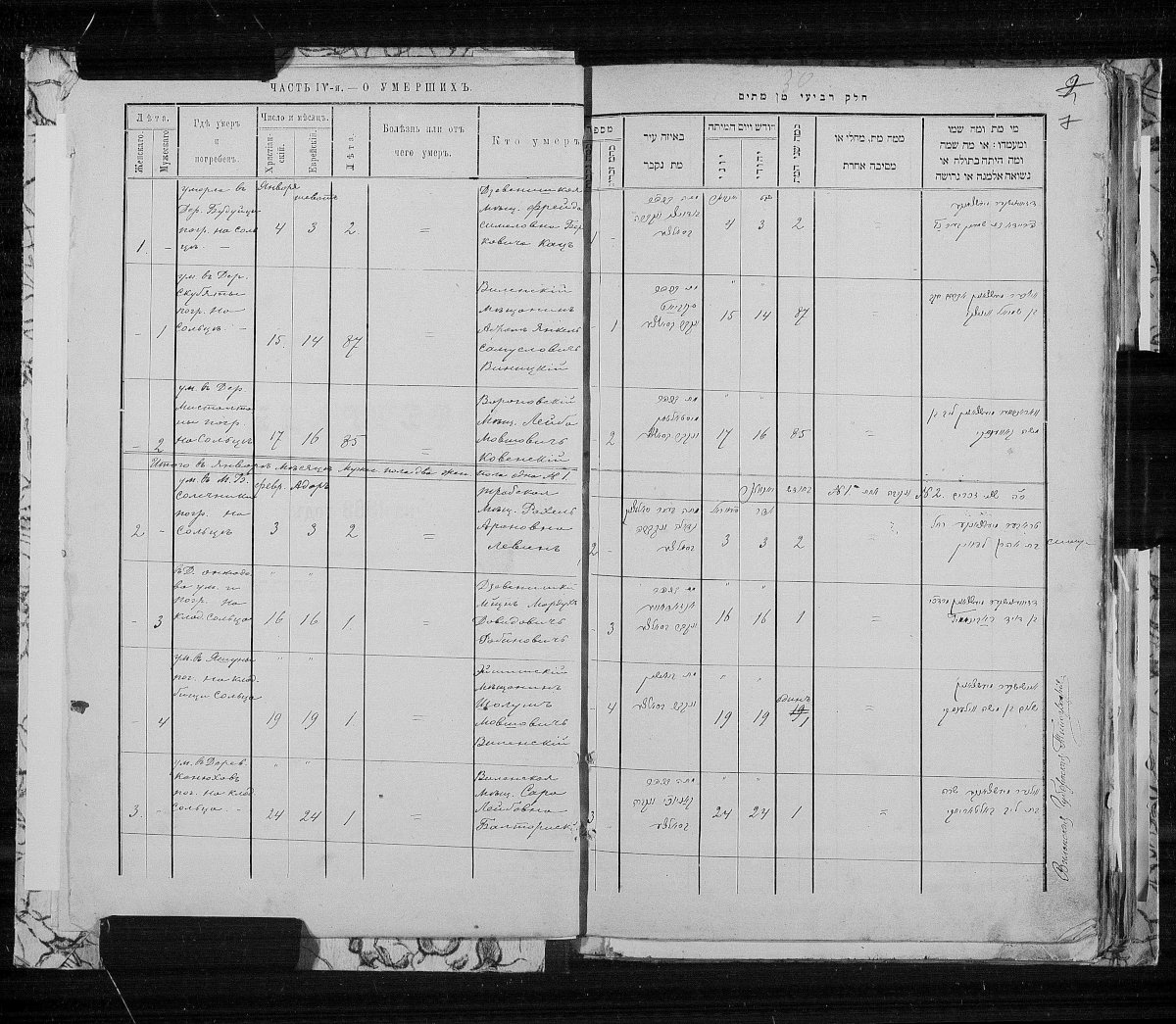

In general, Jewish genealogy records for pre-1917 Lithuania are very similar to those available in other parts of the former Russian Empire. In general, publicly accessible Jewish records in Lithuania exist from the late 1700s through the interwar period. Lithuanian Jewish Vital records began to be kept in 1835 and include birth, marriage, and death records. Unfortunately, Jewish vital records for many towns are highly fragmentary, with relatively few surviving years. Additionally, few cemetery records from Lithuania have survived, although the remaining Jewish cemeteries are currently being catalogued by the Litvak Cemetery Catalogue project. In addition to vital records, Jewish genealogy records for Lithuania include revision lists, lists of draftees, tax records, and voters’ lists for the early twentieth century Russian Duma.

During the interwar period, the newly independent Lithuanian government created a system of internal passports. All residents of the country over the age of 17 were required to obtain passports. Not intended for international travel, the documents served as a means of identification and as legal proof of eligibility to remain in the country following its independence from Russia. The passports and their application files include birthdates, birthplaces, address histories, copies of vital records or revision lists (the originals of which may have been lost), and more. The files often contain photographs of the individual.

In addition to internal passport files, the Kaunas archive contains a file of police records with relevance to Jewish genealogy. The material of primary Jewish interest in this collection dates to 1916. The most relevant of these Kaunas police files relate to political activity of Jewish socialists, wartime activities of the local Jewish community, and petitions for compensation of damages stemming from wartime confiscation of Jewish property.

Where to Find Records

In addition to Family Search and JewishGen, an important place to start research for Jewish genealogy in Lithuania is LitvakSIG. Begun in 1997, LitvakSIG focuses on primary source research on the Lithuanian Jewish community and has indexed more than 2,500,000 records. LitvakSIG has merged with JewishGen, and its search results are available on the JewishGen main page.

For records which are not available online, access is through Lithuanian archives. As is the case with other countries in Europe, older records, which do not fall under privacy laws, are housed in state archives. In Lithuania, the two primary state archive branches with genealogical information are located in Vilnius and Kaunas. Younger, postwar records with privacy restrictions are stored in the Lithuanian Central Civil Register Archives.

In addition to government archives, the Jewish Museum in Vilnius maintains an important collection of Holocaust records. Additionally, the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York maintains a large number of records of Jewish genealogical interest. Other important collections with relevance to Lithuania are housed at the Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People in Jerusalem.

Challenges in Researching Jewish Genealogy from Lithuania

To get the best quality genealogy research, working from primary sources—rather than relying only on secondhand indexes or transcriptions—is critical to building as accurate and complete a picture of one’s family as possible. Unfortunately, the language barrier can make working with these documents extremely challenging for Jewish families from Lithuania.

Since Lithuania was administered as a part of Russia between 1790s and World War 1, the vast majority of genealogical records are in Russian. Additionally, many pre-World War 1 vital records are written bilingually, with one side in Russian and the other in Yiddish or Hebrew. Interwar documents for most of today’s Lithuania are written in Lithuanian, while those for Vilnius and surrounding areas are in Polish.

Complicating the matter even further, nineteenth-century Russian- and Yiddish-language records are written in historic scripts. These archaic cursive handwriting styles, entirely different than modern handwriting, require specialized training to read. For records from Lithuania and other areas of the former Russian Empire, reading the original records in their original languages—critical to genealogical research—can only be accomplished through familiarity with these old handwriting systems.

Summing Up

Lithuanian Jews have distinguished themselves over a history spanning nine hundred years. Genealogy records document the history of most Jewish families from Lithuania over a period of nearly two centuries. Although challenging to use, these records hold the story of our past. With a bit of luck and a lot of persistence, tenacious researchers can unlock the myriad secrets they hold, bringing their family stories to life.