Researching Jewish Families in Galicia

For Jewish families from the southern part of historic Poland (known as Galicia), a wealth of historical information is available. Information sources including vital records, population surveys, business transaction registers, and other sources help shed light on many Galician Jewish families going back centuries. Read on to discover more about these manifold sources and the challenging yet rewarding process of using them to research Jewish genealogy in Galicia.

What Is Galicia?

When Austria, Prussia, and Russia took territory from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1772, a large portion of southern Poland was annexed to the Austrian Empire. Known as Galicia, this region became the largest, poorest, most ethnically diverse, and most heavily Jewish province of the Austrian Empire.

In the third, final partition of Poland (1795), Austria took additional territory which came to be known as West Galicia. Originally administered separately, West Galicia was formally annexed to Galicia in 1803. However, Austrian rule in this region lasted less than two decades. During the Napoleonic Wars, Napoleon transferred West Galicia from Austria to the Duchy of Warsaw, a political entity he had created out of much of the Prussian Polish partitions. After the Congress of Vienna, West Galicia became part of Congress Poland, while Galicia proper remained part of Austria until World War 1.

Unlike the case with Russia, significant numbers of Jews had already lived in the Austrian Empire for centuries prior to its annexation of Polish lands. Prague and surrounding areas of Bohemia were one of the largest centers of European Judaism from the Middle Ages; Jewish culture there reached its full flowering in the 16th through 18th century under Hapsburg rule. In addition, Hungary had an important concentration of Jews.

Despite the prior existence of Jews in Austria, the incorporation of former Polish territories into the Austrian Empire in 1772 was a watershed moment in the history of Austrian Jewry, bringing large numbers of Jews into the empire for the first time. In the nineteenth century, Galicia had the second largest population of Jews in Europe, second only to Russia.

In the wars for Polish independence following World War 1, Galicia was reincorporated into Poland. During World War 2, the Soviets initially occupied eastern Galicia while the western area was invaded by Nazi Germany in 1939. The entire territory came under Nazi control following the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941. In the postwar years, East Galicia was absorbed into the Soviet Union while West Galicia remained part of Poland. Today, the region is split between southeastern Poland and western Ukraine.

Genealogy Records for Jewish Families from Galicia

Vital Records

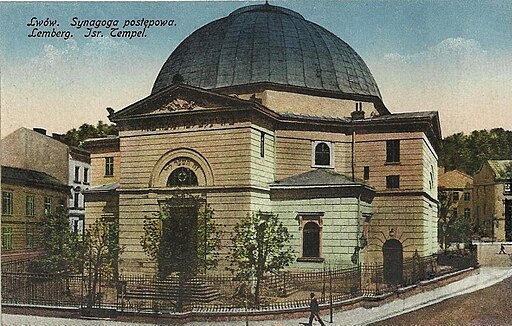

By law, vital records were required to be created in Galicia beginning in 1784. Originally, the Catholic Church was supposed to be responsible for maintaining vital records for non-Catholic populations. However, few Jewish records have been found in Catholic record books from this period. Moreover, in the early days of Austrian rule, the quality and coverage of vital records in many towns was poor. Despite the 1784 law, most cities and towns began keeping records during the course of the 19th century. Large cities like Lviv (Lemberg) began shortly after 1800, while smaller towns began doing so in the mid or even late 19th century.

Census-like Lists

A decade after Austria took control of Galicia, Emperor Joseph instituted a survey of his new holdings. Called the Josephine Survey, the document lists heads of household, house numbers, town boundaries, and a variety of financial information. This survey was carried out between 1785 and 1788. Several decades later, Emperor Francis I ordered a second land and real estate survey in 1817. For more details on these surveys, see https://www.geshergalicia.org/projects/josephine-and-franciscan-surveys-project/.

Other Records

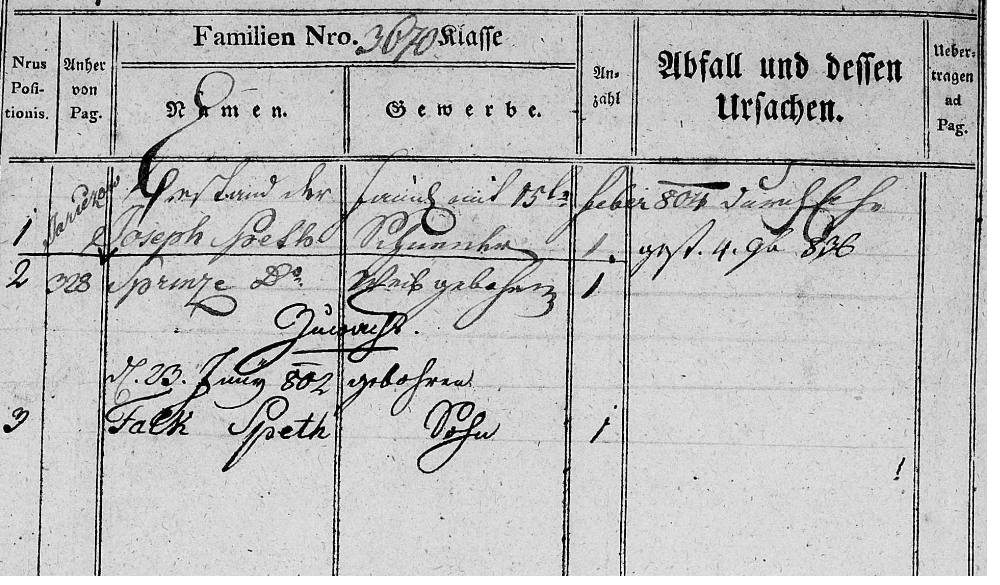

While vital records from the earliest decades of the 19th century exist for Lviv (the capital of Galicia), they are frustratingly vague, carrying little information beyond names, dates, and parents. Supplementing these early records is a set of books for the city of Lviv initially created during the period 1795 through 1804; records for some families continue through the 1840s. The information contained in these family evidence books is not only slightly older than the oldest metrical records but is far more detailed, listing exact birth dates, death dates, marriage dates, maiden names, and occupations. Unfortunately, the books are written in Kurrentschrift and are extremely difficult to read, even for specialists.

Beginning in 1780, the Austrian government began documenting real estate, moneylending, and other legal and financial transactions. These records were kept by the State Registrar Department through the late nineteenth century. In Galicia as in many other places, Jews were highly active in commerce and the professions, so they are well represented in these records. Termed the Tabula Registers, these documents provide valuable clues to modern genealogical researchers. They are housed in the Ukrainian State Archives in Lviv and must be researched onsite. For more information on the Tabula Registers, see https://www.geshergalicia.org/galitzianer/tabula-registers-an-untapped-genealogical-resource-in-the-lviv-archives/ (subscription required).

Several other documents exist with genealogical value for the Jewish community of Galicia. In Lviv, school lists are available which list the names of Jewish students in each class, beginning in the year 1797. Additionally, tax registers are also available for some locations. Moreover, some locations maintained listings of residents which provide household members’ names, dates and places of birth, parents’ names, religion, occupation, and more. Several important directories exist for Krakow. One such document lists Jewish males eligible to vote in elections for Jewish community leaders in 1883 and 1929, while another provides membership rosters for five synagogues in the early 20th century. Finally, late nineteenth-century business directories and early twentieth-century telephone books complement the other available records.

How to Research Jewish Families in Galicia

The best places to begin research on Jewish families from Galicia are Gesher Galicia and JRI-Poland. It is necessary to use both databases, because they include information taken from different sources. Gesher Galicia’s database takes its data from archives in Ukraine, while the information in JRI-Poland comes from Polish archives. Because archival records moved around between countries in the postwar years, various genealogical records for the same family in the same town might be housed in archives in both countries. Moreover, JewishGen, the online center for Jewish genealogy, links to both Gesher Galicia and JRI-Poland as well to many other smaller databases.

Recently, JRI-Poland has begun to display links to results from Gesher Galicia on its own search pages. Even still, it is a good idea to check both search engines because of the way their various filters and advanced search techniques work.

Once you have identified records of interest via Gesher Galicia, JRI-Poland, and/or JewishGen, you will want to examine the original records. To access them, the best bet is to start with the Family History Center. Records which are unavailable at the Family History Center may be available online through the Polish Archives. To access records directly from the Polish Archives, use Szukajwarchiwach. Other Polish records are available online at Genbaza and Skanoteka. For these sites, the ability to research in Polish is extremely helpful. You can use translation, but results are likely to be significantly better if you are able to understand the original version. Finally, for records which are not available anywhere online, it is necessary to contact the Polish Archives directly to request a scans of the records you would like to see.

Unique Problems for Researching Jewish Families in Galicia

One of the more challenging problems of researching Jewish families in Galicia is language. Austria annexed Galicia from Poland in 1772, so official records were kept in German. However, in 1867, as part of the establishment of the dual Austro-Hungarian Empire, Galicia officially received autonomy. As a result, many records from after 1867 are in Polish rather than German. As a result, it is necessary to have proficiency in both languages to effectively perform genealogy research in Galicia. Moreover, prior to 1940 German handwriting was written extremely differently than it is today. This historical handwriting (called “Kurrentschrift”) cannot be read without special training, even by native Germans.

An additional complication for researching Jewish families from Galicia comes about from a particular issue having to do with Jewish marriages. In the late 18th century under Austrian Empress Maria Theresa, Jewish marriages in Galicia were strictly regulated. Only the oldest son in each Jewish family was allowed to marry, while younger sons were not able do so until the oldest one died. In addition, Austrian authorities placed onerous, discriminatory taxes on Jewish marriages and imposed written tests in German literacy and moral ethics. The antisemitic purpose of these restrictions was to deliberately limit the size of the Jewish population.

As a result of these discriminatory laws, Jews often chose to get married religiously but not civically. Although the practice was technically illegal, it was often overlooked. The children of such marriages were technically considered illegitimate by the Austrian state and were supposed to receive the surnames of their mothers rather than their fathers. However, sometimes these children did receive their fathers’ surnames. In many families, some siblings may have been registered under each surname.

As time went by, many of these restrictions and fees were loosened. The literacy and morality tests were abandoned early in the century, and the outright ban on younger children marrying was lifted in 1831. Concurrently, as Jews became more integrated into the national economy and came into prominence in commerce and the professions, civil marriage became important. In order for people to prove they were who they said they were when applying for business or professional licenses, attending higher education, or inheriting property, they were frequently required to provide their parents’ marriage certificates.

To give their children access to these benefits, many older couples chose to receive civil marriages in the late 19th century, often decades after having married religiously. When they did so, annotations were frequently made in their adult children’s birth records marking them as legitimate and changing their birth surnames. However, even in the late 19th century, far fewer Jewish marriage records exist than would be expected given the size of the Jewish population.

Summing Up

For the century and a half of its existence, Galicia was the thriving home of one of the preeminent Jewish communities in Central Europe. Overcoming persecution, Galician Jews integrated themselves into their communities and made immeasurable contributions in business, medicine, architecture, law, the arts, and more. Thanks to records including vital records, population surveys, financial transaction registers, and other valuable documents, the history of Galician Jewish families lies waiting to be uncovered.