Belarus

Researching Jewish Families from Belarus

As one of the main regions of Jewish settlement in the former Russian Empire, Belarus played a vital role in the history of the Jewish people. Although a relatively small country, Belarus was home to the ancestors of significant numbers of American Jewish families. While not necessarily easy to research, documents in Belarus preserve the history and legacy of many of these families. Read more to learn how to research the history of Jewish families from Belarus.

Historical Background

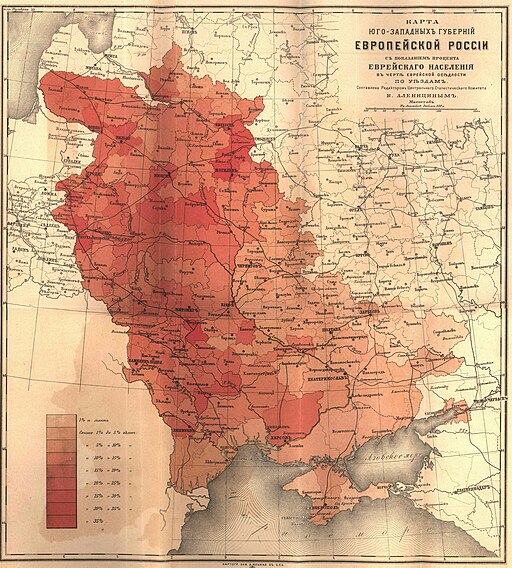

Jews have lived in the territory that would eventually become Belarus since the late 1380s, when the area became part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. The first Jews to arrive in the future Belarus migrated to the region from Germany and Poland, settling in the towns of Brest and Grodno. As a center of trade between Lithuania, Poland, and Russia, the area soon became attractive to Jewish immigration. Additionally, Jews enjoyed court protection in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Absentee landowners in rural areas rented inns to Jews, while those in more urbanized locations entrusted private villages and towns to Jewish administers. Jews eventually came to comprise the majority of the population in Minsk, a large majority in Pinsk (72.4%), and a majority or plurality in several other cities of current-day Belarus. Historically, the most important Jewish population centers in the region were the cities of Minsk, Mogilev, Orsha, Vitebsk, and Polatsk.

Modern-day Belarus remained a part of Lithuania (including during its integration into the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth) for nearly four centuries. Along with the rest of Lithuania, Belarus became part of the Russian Empire with the partitions of Poland-Lithuania in the late eighteenth century. Prior to this event, very few Jews had lived in Russia, and an entire legal framework was created to deal with the empire’s new Jewish population.

The most prominent restriction placed on the Jewish community in Russia was a 1791 law forbidding them from living farther east than a prescribed region termed the Pale of Settlement—a constraint which remained in force almost continually until the 1917 revolutions. Additionally, Jewish merchants were forced to pay a tax rate twice as high as Christians, while the community also faced discriminatory taxes on inheritance, building leases, alcohol, cattle, other industries, and the “right” to wear Jewish clothing. Moreover, the official Jewish community self-governance was forced to help implement these antisemitic laws.

Under Tsar Alexander II in the mid to late nineteenth century, conditions for Jews in Russia temporarily improved. Certain wealthy or prominent Jews were granted permitted to reside outside the Pale of Settlement at various times—government workers with academic degrees, prominent merchants, and individuals with in-demand occupations (artisans, mechanics, or distillers) were allowed to live in Moscow and St. Petersburg beginning in the 1860s, while Jews holding academic degrees were allowed to reside anywhere in the Russian Empire by 1879. During this time, Jews were permitted proportionate representation on town councils, even in towns where they constituted the majority.

By the late nineteenth century, however, the loosening of restrictions on Jewish life in Russia began to reverse. In 1879, the same year in which Jews with academic credentials were granted freedom of residence in Russia, Jews in the Pale of Settlement became limited to a maximum of one-third of the total seats on local governing bodies regardless of their actual proportion to non-Jewish residents. Two years later, Tsar Alexander II was assassinated. Although the assassination had been planned and carried out by anarchists and Polish nationalists, and despite the fact that Russian Jews had venerated Alexander because of his support for Jewish rights, the assassination was falsely blamed on Jews in the popular Russian imagination.

For several decades following the assassination, violent pogroms killed thousands of Jews throughout the areas of the Russian Empire in which they lived. Moreover, under the new tsar Alexander III, further legal restrictions on Jews were imposed. In 1887, strict Jewish education quotas were introduced along with stricter adherence to earlier residence requirements. In 1891, 20,000 Jews from Moscow (two thirds of the city’s Jewish population) were expelled to the Pale of Settlement, many in chains.

In addition to political repression, the Russian Empire was relatively economically underdeveloped, particularly in rural regions. In Belarus, local populations faced extreme poverty. As a result, many Belarusian Jews in the early nineteenth century migrated to southern parts of today’s Ukraine, a region that the Russian imperial government had captured from the Ottoman Empire and in whose economic development it had more heavily invested. In the wake of pogroms in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, many Jews from Belarus immigrated to the United States.

During the interwar period, eastern Belarus became part of the USSR while western Belarus became part of newly independent Poland. Emigration continued from the Polish-controlled parts of Belarus, as did more traditional forms of Jewish life; both of these were heavily curtailed in Soviet areas. The area was invaded by Nazi Germany in 1941 during World War 2 and by the Soviets in the war’s final years. Tragically, the vast majority of the Jewish population of Belarus was killed in the Holocaust. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, many Jews from the eastern part of interwar Belarus who had evacuated to the interior portions of the Soviet Union returned to Belarus. The emigration of Belarusian Jews, mainly to Israel, resumed in the 1970s and continued into post-Soviet days.

Openly Jewish life resumed in Belarus following post-Soviet independence. By the mid-1990s, approximately 40,000 Jews remained in the country, primarily in Minsk, Bobruisk, Gomel, Mogilev, and Vitebsk. More recently, Jewish emigration from Belarus to Israel has increased following the 2020-2021 protests and especially in the wake of the country’s role in supporting Russia’s war against Ukraine.

What Genealogy Records Are Available for Belarus?

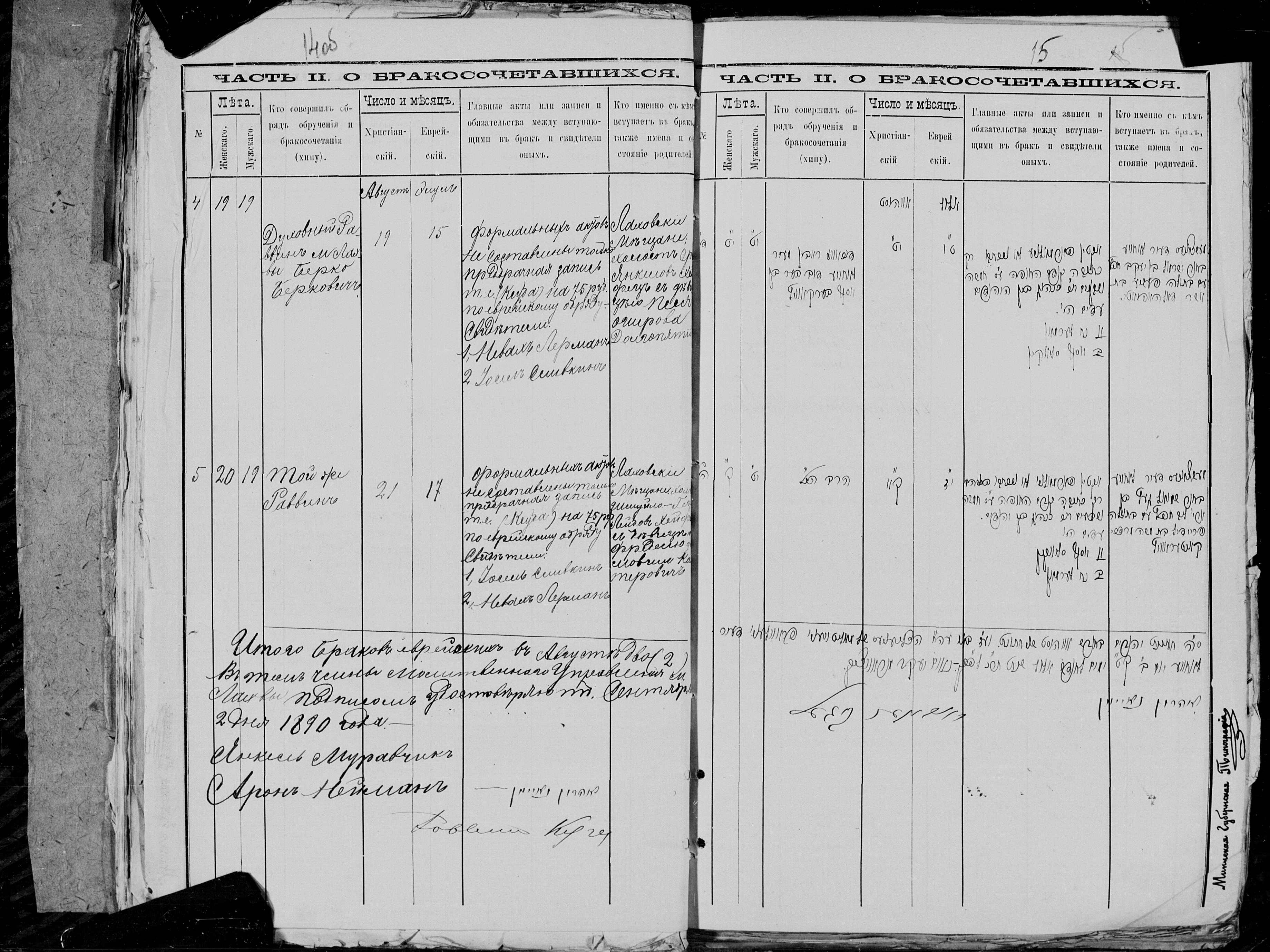

As with Lithuania and Ukraine, the types of records available for Jewish families from Belarus are similar to those in other areas of the former Russian Empire. In Belarus, Jewish vital records (also called “rabbinate records”) were compiled annually from 1835 through 1917. Unfortunately, many of these rabbinate records are fragmentary or no longer exist. Due to the paucity of these vital records, it can be very hard to locate specific people of interest.

Complementing the fragmentary vital records, revision lists and tax records help fill out the picture of nineteenth-century Belarusian Jewry. In addition, kahal records were created for internal use by the local Jewish community. These documents frequently include synagogue member lists, records of financial contributions to the Jewish community, and election lists for Jewish religious positions.

For the city of Minsk, many interesting documents exist. Among these are 1858 revision lists, 1894 family lists, lists of Jews who incurred losses in 1905 pogroms, and voters lists in the 1917 elections. Additionally, other documents housed in the Minsk archives include lists of permissions to erect buildings, business license applications, and passport registers. One of the most genealogically important records for Jewish families from Minsk is the military draft lists, covering the period 1812 through 1917.

For Vitebsk, relatively few vital records or revision lists have survived. However, family lists and lists of Jewish merchants for the years 1874 through 1919 have survived. In addition, a survey of Jews living in Vitebsk guberniya was carried out in 1910.

Unfortunately, most records for the city of Grodno were destroyed during World War 2. The most important surviving records there are the various revision lists taken periodically through the nineteenth century.

Where to Find Records

In addition to the Family History Center and JewishGen, Jewish genealogy records for Belarus are located in Belarusian archives. The most important archives in Belarus for Jewish genealogy are the National Historical Archive of Belarus in Minsk and the National Historical Archive of Belarus in Grodno. In addition to these two, records from the Soviet period (1918-1990) are held in the State Archives of Minsk Oblast. For western Belarus, the Branch Archive of Minsk Oblast in Molodechno holds Polish records from 1919-1939 and Soviet records from 1939-1990. Finally, provincial archives in Grodno, Brest, and Gomel also hold some records of interest to Jewish genealogists.

Outside of Belarus, records of interest are located in the YIVO Archives in New York City and in several archives in Israel. Online, some digitized documents may be found on JewishGen and Family Search.

Challenges of Researching Jewish Genealogy in Belarus

In addition to the challenges of language and historic script, locating Jewish records for Belarus can be difficult. By international convention, archival records are supposed to be kept in the same modern countries where the cities or towns they pertain to are currently located. However, records for some areas of Belarus are currently held in archives in Vilnius, Lithuania.

In addition to the challenge of locating material, international sanctions on the government of Belarus create bureaucratic challenges. According to the latest sanctions, United States citizens are currently permitted to send money to Belarus to export information but not to create new information. In practical terms, this allows US-based researchers to pay individuals or archives to send scans, but not to hire researchers in Belarus to analyze them. However, the mechanics of sending money internationally to Belarus has been severely complicated by the sanctions. For more details on United States sanctions on Belarus, see https://ofac.treasury.gov/sanctions-programs-and-country-information/belarus-sanctions.

Summing Up

Despite the inherent challenges in working with historic materials handwritten in old Russian, the many genealogy resources available for Belarus can unlock many of the secrets of our families. Census records, conscription lists, vital records, and other resources all carry hints of who our ancestors were and what their lives may have been like. Whether you ultimately decide to research your family yourself or hire me to research for you, the story of your family lies waiting to be uncovered.