Finding Your Russian Jewish Roots

If your family is like most Jewish families, you were probably told when you were younger that your family came from “Russia.” This is not at all surprising. In the late 19th and early 20th century, Russia had by far the largest Jewish population in the world. For example, in the year 1900, a survey of world Jewish demographics estimated that nearly 50% of the entire global Jewish population was living within Russia—a figure more than three times higher than the country with the next highest Jewish population (the United States). In fact, this figure came 20 years into a mass Jewish exodus from Russia that remains one of the largest migrations in modern history.

Many important resources exist for tracing Jewish families from Russia. In addition to the standard “bread and butter” genealogical sources (birth, marriage, and death records), important resources for studying Russian Jewish families include revision lists, census records, police records, city directories, and other documents. These documents may help you to uncover more of your Russian Jewish family past than you likely would have thought possible. Moreover, because of territorial changes affecting the Russian Empire and the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991, these documents are relevant to Jewish families from many areas now outside of Russia, including Belarus, Lithuania, Poland, and Ukraine.

What Resources Are Available for Jewish Genealogy from the Russian Empire?

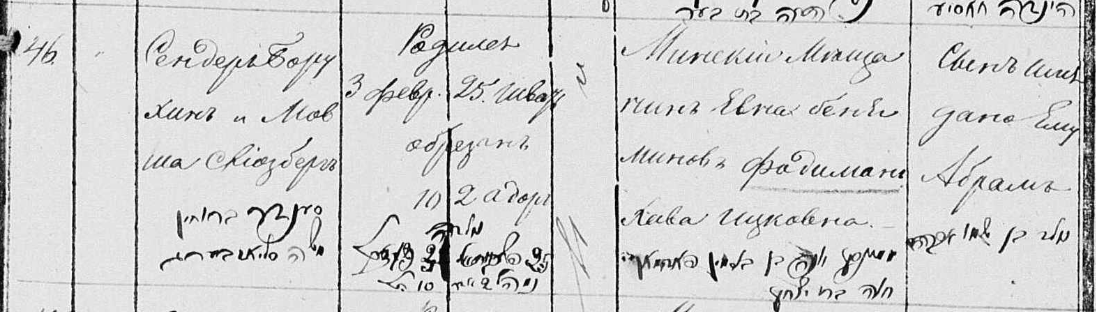

Vital Records

In most parts of the former Russian Empire, Jewish communities began to keep vital records in 1826 and continued doing so to modern times. Theoretically, each time a person in the Jewish community was born, married, or died, family members would attest to the event and a record was kept by local officials—although sometimes the events were registered years after the fact while in other cases they were never registered at all. Jewish vital records in Russia were collected by government-appointed state rabbis (whose function was entirely different from pulpit rabbis) and were maintained by local Jewish communities. While most medium-sized towns kept their own records, Jewish records in outlying villages were often grouped together along with those in the nearest town.

Unfortunately, vital records in many Jewish communities in the former Russian Empire are fragmentary. Jewish communities in Lithuania, Belarus, and much of Ukraine tend to have much less coverage than Poland, with far greater record loss due to fires, wars, or destruction from other causes. In many towns, vital records from only a few years of the nineteenth century survive.

A typical example of the fragmentary nature of vital records in the former Russian Empire is the town of Sumy, Ukraine. Although Jewish vital records were collected since the 1820s, the only surviving ones from this town prior to 1880 are birth records from the year 1869, marriage records from 1869, and death records from 1879. If your ancestors lived in Sumy in the early or mid-nineteenth century, only vital records for those family members who happened to have been born or married in 1869 (or had these events registered in 1869) or to have died in 1879 still exist. While surviving records from 1880 through 1920 are more extensive for this town, plenty of years during that time period are also missing.

In most countries of the former Russian Empire, whatever vital records from the 1820s through 1920s that still exist are kept in centralized government archives. Records from more recent times are stored separately in local offices.

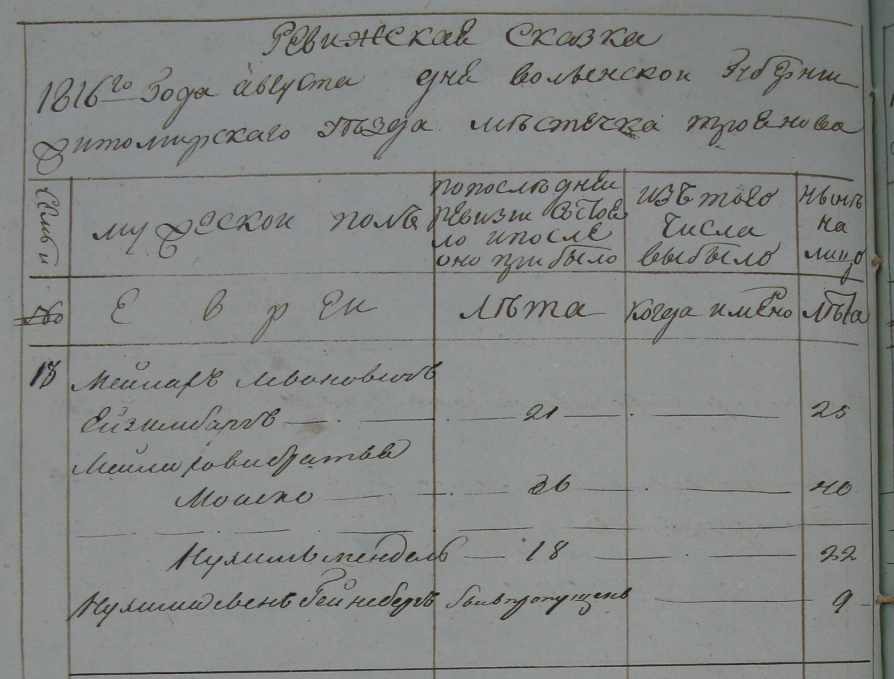

Revision Lists and Other Lists

The low coverage of Jewish vital records for most parts of the Russian Empire is disappointing, to say the least. Fortunately, however, a variety of other sources exist. Taken together, these additional sources of information can help fill in the holes left by missing vital records. The most important of these additional sources, and the most frequently used in Jewish genealogy research, are revision lists.

In the early eighteenth century, Tsar Peter the Great decided that Russia needed a better way of collecting information on its subjects. As part of his modernization of the country, he had the Russian government carry out a series of census-like surveys called revision lists. Aimed at streamlining its collection of taxes as well as carrying out its military draft policy, these lists were created periodically during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries throughout most of the Russian Empire.

In total, ten revisions were taken, although the ones of primary interest for Jewish genealogy are the last six (carried out in 1794-1808, 1811-1812, 1815-1825, 1833-1835, 1850-1852, and 1857-1859). Because of the vastness of the Russian Empire, each revision list took multiple years to complete. Additionally, they were continually updated with new information over a period of many years until the next official revision list was carried out; updates to the lists were compiled as supplemental revisions. The final revision was updated continually throughout Russia up to 1874 and in isolated places as late as 1908. Revision lists were not carried out in Russian Poland, and did not include members of social classes which were exempt from taxation.

Revision lists provide information on many Jewish residents of the Russian Empire, including name, age, occupation, wives’ names, and children. Frequently, multiple generations of a single family were living in the same household and are listed together. Unfortunately, the revision lists do not typically provide married women’s maiden names. For more details on Russian revision lists, see Boris Feldblyum’s article (http://www.bfcollection.net/fast/articles/ruscensus.pdf) and the excellent study by Joseph Everett (https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5267&context=facpub).

In addition to revision lists conducted by the imperial government, local authorities created Jewish family registers. Taken biannually starting in 1844, these documents list all Jewish families in individual towns. Alphabetical lists of Jewish heads of household were also compiled periodically at irregular intervals. Beyond these, recruitment lists, which list males subject to military conscription, also serve as important sources of information on Jewish families from the Russian Empire. Finally, Russia conducted its first and only official census in 1897, although large amounts of it have been destroyed.

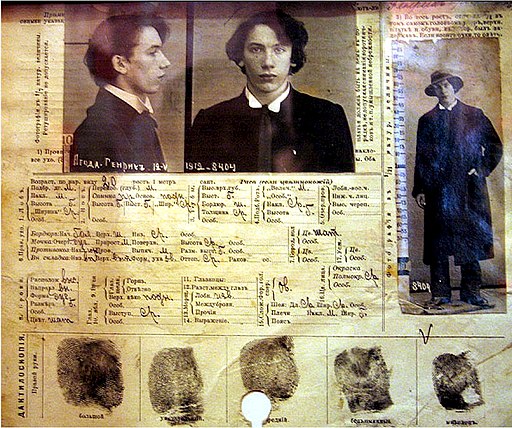

Police Records

After 1844, both district and city police began to keep files on local Jews. These files often include official residence permits, petitions to start businesses, internal travel passports, and other documents. Later in the late 19th and into the early 20th century, Jews came to be even more heavily scrutinized by the imperial government due to their emerging Socialist and Zionist political leanings. As a result, a large number of the police documents on Russian Jews date from this period. Police files from the 1880s through the 1917 revolution also include lists of pogrom victims and perpetrators.

The collection, holding records on hundreds of thousands of Russian Jewish individuals, is held by the Russian State Archives in Moscow. Theoretically, this archive holds imperial, Soviet, and early post-Soviet records dating from 1800 through 1993. Unfortunately, due to Russia’s ongoing illegal, barbaric invasion of Ukraine and the resulting geopolitical tensions between Moscow and the West, it is unlikely that American genealogists will be able to consult these records any time in the foreseeable future.

Other Records

Russia remained the last absolute monarchy in Europe, its tsars maintaining absolute power almost up to World War 1. However, beginning in 1905, a second house was added to the Russian State Council. Unlike the upper council, this lower house—termed the “Duma”—was comprised of elected representatives. All men in the Russian Empire over age 25 were eligible to vote for representatives to send to this lower house. Lists of eligible voters were published in official government regional newspapers in 1906, 1907, and 1912; many of these lists survive to the present day.

In addition to voters’ lists, numerous city, province, and empire-wide business directories were printed in the late 19th and early 20th century. Since Jews were active in commerce and the professions, these publications contain a wealth of information about Jewish individuals. Many of these directories can be searched electronically via Genealogy Indexer.

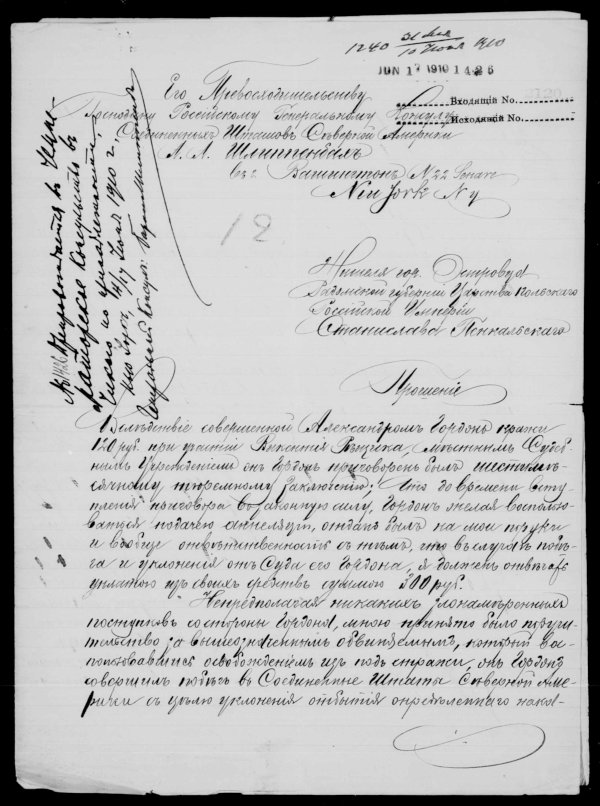

An additional, often overlooked source of information on Russian Jewish family history are the Russian Consular Records. After individuals left Russia, in many cases they remained dependent on the Russian state for passports, proof of citizenship, and similar issues. Additionally, the Russian state began controlling emigration in 1892, so individuals desiring to leave the country after that date would have been required to apply for government permission to do so.

Correspondence between the Russian government and Russian immigrants in the United States exists for the years 1862-1928. The record collection includes passports, passport applications, visas, nationality certificates, and other similar documents. Existing records often include the individual’s complete name, date, place of birth, names of close relatives in both the United States and in Russia, and the individual’s reasons for immigration. Many later records include photographs. The Russian Consular Records are available at the National Archives and Records Association and at Family History Centers, and are indexed by name of individual.

Summing Up

For the many American Jewish families with origins in the Russian Empire, research can be challenging but rewarding. Documents such as vital records, revision lists, conscription lists, and consular records provide valuable information on our ancestors. However, because of the nature of government persecution in imperial Russia, tracing the history of Russian Jewish families offers a variety of challenges.