But What Does It SAY? How Three Historical Scripts Supercharged My Genealogy Research – Part 3

Knowing so many languages, and developing the ability to read them in obscure historical handwritings, has been immensely helpful in my research—both personal and professional. Here are just a few examples of what I have been able to find in my research. For more details and further examples, feel free to browse other blog entries.

The Case of the Leaky Cups

When researching for a client, I found one of her relatives’ names mentioned in a database I was using. The database provided no information except the person’s name—Chaim Neufeld—and the year (1906). It did, however, contain identifying information on how to locate the original record in the Polish State Archives in Warsaw. We had no idea what to expect, although I suspected it might be some kind of census or business record.

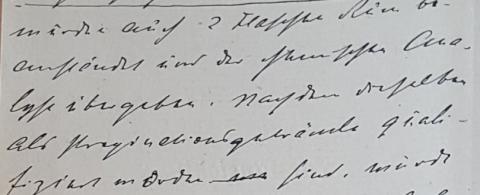

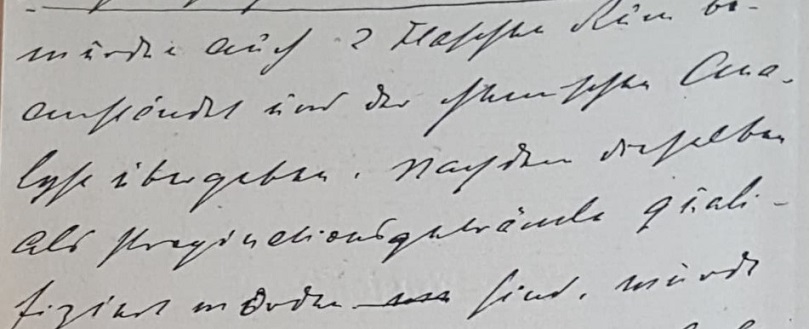

Last summer I had the opportunity to travel to Warsaw to attend the IAJGS conference and to give a talk at the Gesher Galicia AGAD Symposium (see: link). I also took the opportunity to conduct research at the archives. During my time there, I was able to locate the original record for Chaim Neufeld whose name I had found in the database. Far from simply mentioning his name, the document was a full five pages long—all in Kurrentschrift.

The document turned out to be a court case. As it happens, my client’s relative was a tavernkeeper in the town of Probużna, Galicia around the turn of the century. According to the case report, he was accused of using faulty cups, causing the liquor to flow out of them. He was given a fine and later applied for forbearance. Although this gives a perhaps less than flattering picture of Chaim, it still provides an enormous amount of information: his location, occupation, and a glimpse of what his working life may have been like—including the inevitable disputes that frequently arise in any aspect of commerce.

Discovering a Whole New Family

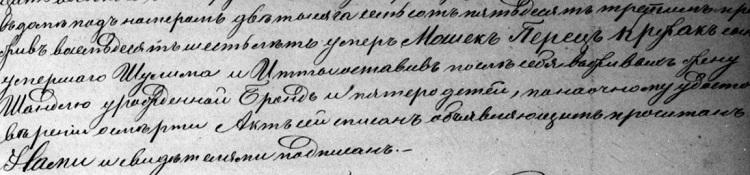

One of the first Russian-language documents I found was my grandfather’s paternal grandparents’ 1894 marriage record. My grandfather knew nothing about them or their family, since they died before he was born and his father had not been close with them. However, once I examined the 1894 marriage document using my Russian language and reading skills, I learned a lot about them: ages, occupations, parents’ names, mothers’ maiden names, even street addresses in Warsaw.

I used the information gained from this document as a basis for further research. Using a combination of databases, archival research, and language skills, I was able to uncover the history of this part of my family going back to c. 1750. For more details, including how I found that my grandfather’s great-grandfather received a bronze medal from Tsar Alexander II, and how my knowledge of old Russian cursive allowed me to connect my family with another one of the same name in a different part of Poland, see https://blog.lostrootsfamilyhistory.com/military-award.

More Details Emerge

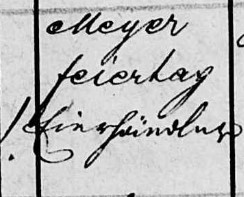

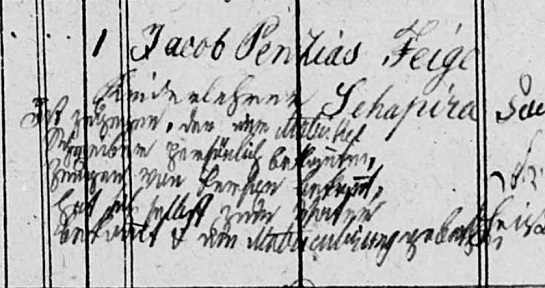

As I have repeatedly stressed, original records often contain significantly more information than database entries. This was certainly the case in my grandfather’s maternal grandparents’ family. For example, one of the first things I learned was that my 4x-great grandfather had been an egg merchant in the 1840s. In fact, this suggests a certain upwards mobility—by 1869 he owned a prominent apartment building on the old market square in Lemberg, capital of Austrian Galicia, and his daughter (!) owned a neighboring apartment building. I also learned that another relative, Jacob Penzias, went from being a schoolteacher to an upholsterer to a horse merchant in the 1830s and 1840s. For all of this and much, much more, see https://blog.lostrootsfamilyhistory.com/about.

How All This Can Help You

The ability to read the original records is invaluable in genealogy research. To reiterate my previous point, original records often provide important details that may be left out of databases. Moreover, many documents are not covered in databases; being able to read and understand them can drastically add to our knowledge of our families’ histories.

Reading the original documents can also be helpful in other ways. It can be extremely beneficial to be able to double-check the work of those who have already done it. Transcription errors by database compilers or other genealogists are not very common but do occur. Working with hundreds of records which may be poorly written or copied, transcribers may be limited in what they can achieve. In any case, four eyes are almost always better than two when working with difficult or archaic handwriting.

Although translation services, including free ones, are often available, there are many cases when it is far more beneficial to integrate translation into research. For instance, when looking through some types of databases, particularly newspapers or metrical records, it is important to be able to determine which results are worth translating and which are extraneous. For example, when searching historical newspapers you may get more than a thousand search results, of which twenty are related to your family. In other cases, you may find OCR (optical character recognition) errors, or simple coincidences.

As another example, you might end up with a large number of results when searching through metrical records for a given surname. It could be quite cumbersome to have each one individually translated before figuring out which ones are related to you. Being able to read the records as you find them is a huge help in compiling extended family trees from metrical records.

As an illustration of the power of simultaneous translation and research, the name “Glina” means “clay” in Polish. When researching for a client, I had to be able to quickly determine which historical newspaper articles were about people selling clay and which ones were about people with the name Glina. Had I been a private researcher relying on translation services, it would have been extremely inefficient to try to get more than a thousand results translated, then wade through the results to figure out which ones related to my family.

Why Hire Me?

Developing the ability to read and understand these historical scripts in German, Russian, and Hebrew was extremely challenging. Although the techniques I used to learn them can work for anyone, they were quite time-consuming. Simply put, learning five foreign languages and multiple writing systems for them may not be for everyone.

Most Jewish families have roots in several countries. If your family is anything like mine (and it probably is), you will have records in a variety of languages. While many genealogists can offer services in German, Russian, or Hebrew, it is quite rare for a single researcher to be proficient in all of these and more.

My proven research and language abilities can potentially uncover fascinating insights about your family, and could save you an inordinate amount of time and effort. To learn more about me, please read my other blog articles, or feel free to visit my website at www.lostrootsfamilyhistory.com. If you would like to contact me directly to find out more or to book a research appointment, you may contact me by visiting https://lostrootsfamilyhistory.com/contact

Add new comment