Working on a Historic Treasure -- Prague Old Jewish Cemetery (Part 1)

The city of Prague is one of the most famous and historic in Europe, attracting millions of visitors per year. Many of these tourists will visit the city’s places of Jewish history—the streets of the old Jewish quarter, the Hebrew clock tower, and the Altneu synagogue (one of the oldest surviving synagogues in Europe, built in 1270).

In fact, Prague is one of the most important locations of Jewish history in Central Europe. Jews have lived there since around the year 900, and the city has been an important center of Jewish learning and culture ever since. It was also an important site of migration—Jews from Prague spread out into many communities in other parts of continental Europe.

One of the most famous locations in Prague is the old Jewish cemetery. More than a tourist attraction, it is a monument to those who came before us and a priceless historical record of this important Jewish community. It was not the first Jewish cemetery in Prague, but became the main one in the late medieval-early Renaissance period. Active from the fifteenth century until the end of the eighteenth, it has tombstones dating from 1439 to 1787. Many illustrious people are buried here, including noted scholars, rabbis, historians, and poets. In total, there are 13,415 surviving tombstones, although many more people are buried here whose tombstones have not survived.

Documenting a Historic Treasure

Though it may seem dry and scholarly, understanding the history of the documentation the Prague Jewish Cemetery is critical to understanding the exciting efforts currently underway. Although the information was written on the tombstones, it had not been gathered into one place or presented in a manner allowing for scholarly study prior to the nineteenth century. A few early attempts to record and preserve some of this information culminated in a book titled Gal Ed, a transcription of 170 tombstones of prominent individuals. Published in 1856, this was the first large-scale effort at providing documentation of some of the people buried in this historic cemetery.

In the late nineteenth century, two scholars went through the cemetery tombstones, documenting everything they found. The more famous of these two was Simon Hock (1815-1887). A businessman and amateur historian who had written the introduction to Gal Ed, Hock worked through existing documentation, studied tombstones, and created an extensive set of notes.

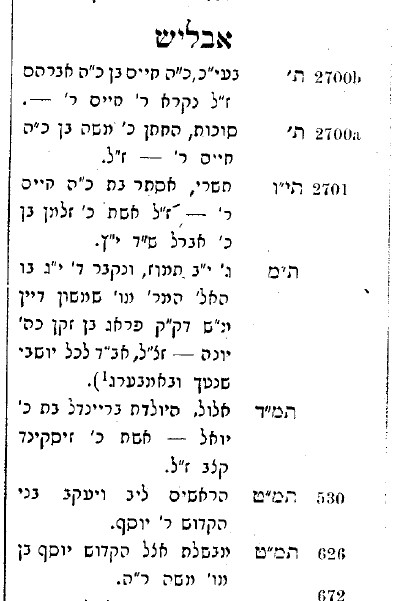

At the time of Hock’s death, his research notes were left in a horrible state of disarray. A few of his notebooks were selected by his friend David Kaufmann, who edited and organized them with the help of the librarian of the Budapest Rabbinic Seminary. Kaufmann compiled these edited notes into a book, which he published in 1892 as Die Familien Prags (The Families of Prague). Four hundred pages long, the book is an extremely important source of genealogical information about the Prague Jewish community. However, it is written entirely in Hebrew (aside from the German-language introduction and title page). Moreover, it is in Rashi typeface, a relatively obscure Hebrew font (see the bottom of https://blog.lostrootsfamilyhistory.com/historical-scripts-2). For these reasons, it poses significant challenges to those wishing to study it.

An Overlooked Treasure

Hock’s work was actually based in large part on the work of Leopold Popper (1826-1885). The two scholars were close friends, and Popper had in fact provided some of his own notes to Hock. A member of the Prague Burial Society, Popper was approached by the chairman of the society, M. A. Wahle, to transcribe all the epitaphs in the cemetery. Between 1875 and 1881, Popper worked methodically, documenting every tombstone inscription he could find—including digging up some that had sunk below ground level. His work came to a total of 2203 pages, and includes word-for-word transcriptions of every tombstone he located. He also compiled a 420-page name index. Although far from perfect, Popper’s index is the most complete documentation available of one of the largest Jewish communities of Europe in the early modern era.

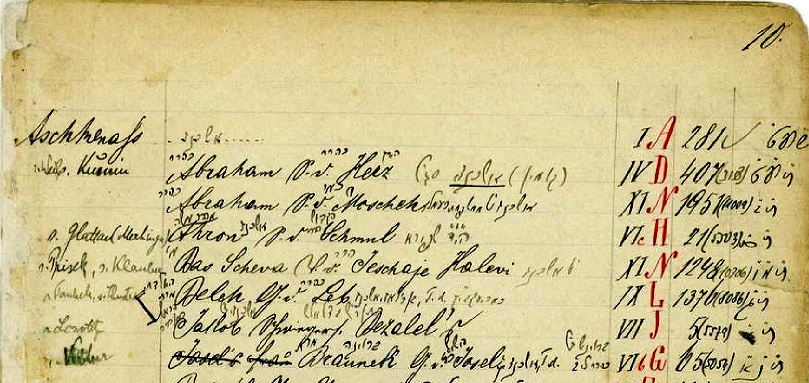

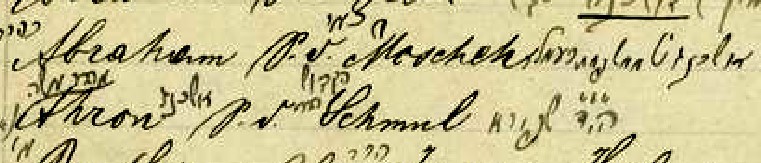

Popper’s work was intended for internal use by the burial society and was never meant for publication. His index, a rough manuscript, includes names transcribed from Hebrew into German, and contains many additional notes scrawled in the margins. It is arranged in alphabetical order by last name, then by first name—although sometimes people are added out of sequence to the top or bottom of family lists as he discovered them (long before the era of word processing). The index also lists the cemetery section and grave number where each tomb can be found. The document is written in a mixture of German and Hebrew—and the Hebrew is written in a unique cursive handwriting that takes quite a bit of getting used to.

This index has been scanned and made available through the Jewish Museum in Prague website (https://www.jewishmuseum.cz/). Through their generosity and hard work, this fascinating document is available for scholars, interested laypeople, and anyone else. Together with Hock’s work, it can yield fascinating insights into a watershed place and time in Jewish history.

Stay tuned until next time for a summary of the work I am doing on this historic treasure.

Note: for more information on the Prague Jewish Cemetery and its documentation, see Daniel Polakovič, “Documentation of the Old Jewish Cemetery in Prague,” Judaica Bohemiae XLIII (2007-2008): 167-192.

Add new comment