When Databases Are Not Enough

In my last post, I talked about some of the astounding implications and possibilities of computerized genealogy, as well as some of its inherent limitations. By now it should be clear that if you want to do some of your own genealogy research, the first step of your search should be databases. Some of the information that can be teased out of them can be quite tantalizing. Yet as we have seen, using them also requires a certain finesse, deductive skills, and plenty of self-education. Even more, there are many situations when using databases might not be enough.

Additional Information

Every day, teams of volunteer researchers are devoting their time to decoding original records and manually adding the information to databases so that it can be easily found. Their heroic efforts should be recognized, appreciated, and applauded. Yet even they cannot do everything. When searching for your family, the information you see on databases frequently does not provide the whole picture.

Examining the original records can often yield interesting or surprising information that is not included on the database. For example, many marriage and death records give occupations, and birth record often provide the father’s occupations. Other times the records indicate that the person lived somewhere other than where the record was from. When examining my great-great-great grandfather’s death record, I noticed the Russian phrase “soldier for the fatherland.”

While this kind of information is sometimes indicated in databases, it is more frequently omitted. In other cases, information from the original records may be mistranscribed. Database compilers are frequently working with tens of thousands of records that may be in German, Polish, Russian, Yiddish, or other languages. They might not have time to enter all information—and even the most dedicated volunteer sometimes makes honest errors. Many confusing details can be resolved by comparing the database entries with the original records. For this reason and many others, the ability to access and read original records can be absolutely critical.

Family Trees

When examining results for a surname search in a particular town, one of the most important tasks is to arrange the results into a family tree. This can be done by using information about the individuals’ parents. When looking at the search results, you may notice that some of the people shared the same parents. These were siblings, and can be easily arranged into a simple tree diagram. If you are lucky, the siblings’ parents will also have birth, marriage, and/or death records in the database, which will tell you who their parents were. Other individuals in the database results may share those parents, and eventually you can assemble the entire list into one or more family trees. There will usually be holes, but it’s often enough to give you the general outlines of your family tree stretching back surprisingly many generations.

However, sometimes database results do not provide the information necessary for building trees. This frequently happens when records are written in old Russian or old German cursive, especially when the handwriting is particularly messy. In some cases, databases will only provide the first and last names, leaving out information on parents. This can completely hamper our efforts at constructing trees. Without knowing the parents, we simply have no idea how the person relates to other people on our list.

In other cases, records in database results might not include ages. This can be particularly frustrating for death records. If Jacob Niedermeyer died in 1872 but the database does not provide the age, he may have been born in 1870 and been part of the fourth generation since the family’s arrival in the village—or he may have been born in 1810 or even 1780 and been one of the family’s founding members. Without an age of death, there’s no way to tell, and it’s impossible to place him on a tree.

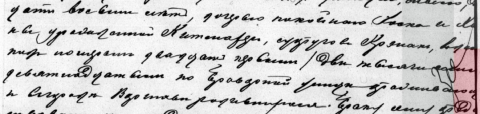

Here’s an example of this that happened to me. When researching for a client, I found approximately 50 individuals with the same last name in one particular village. I wanted to arrange them into a tree as the basis for further research, but the database did not provide any information on parents. From the database alone, I had no way to determine how any of them were related. Fortunately, I was able to access images for all of the original records, which were handwritten in old Russian cursive. Because I am proficient in this script, I was able to examine each and every one of the records. They provided all the relevant information, so I was able to identify siblings, parents, grandparents, and cousins. The death records provided ages, so I was able to work out which of them were children, which were adults, and the approximate birth dates of their parents. Ultimately, I succeeded in arranging all of the individuals into a tree. I never would have been able to accomplish this without reading the original records—and without being able to read nineteenth-century Russian cursive.

Connecting Multiple Families

Here’s another great example of what reading the original records can teach us. In my own family, I was researching the Grajewski family from Warsaw. My research had led me to my 3x-great grandfather Josek Grajewski, son of Gerszon Grajewski. I also found another Grajewski family, from Bialystok, with several similar first names as mine: Joseph, Rubin, and Gerszon. These Bialystok Grajewskis were the children of Szmuel, who was about ten years younger than my 3x-great grandfather. I suspected that there might have been a connection because of the similar first names—Jewish families often name children after deceased ancestors, so you tend to get a lot of first, second, or third cousins with very similar names. However, Grajewski is a somewhat common last name in this region of Poland, and Bialystok is nowhere near Warsaw. I could not be sure that this was anything more than an interesting coincidence.

When conducting archival research in Poland, I found a primary document (one that was not available in any database) stating that Josek had originally come from a town called Stawiski. Going through images of the original records for the Bialystok Grajewski family (which were available online), I found that Szmuel Grajewski was also originally from Stawiski, and that he, too, was the son of Gerszon! I had made my connection! Apparently after growing up together, the older brother—my ancestor—migrated 100 miles to the west while the younger brother travelled 60 miles to the east. I am hopeful that future research will allow me to locate living descendants of this Bialystok branch of my family I never knew I had.

My Russian language skills, reading ability, and tenacity have given me profound insights that went far beyond what the database could have provided. Had I not been able to read original Russian-language records, and had I not found the extra document in the Polish State Archives, I never would have discovered that my ancestor was from Stawiski—let alone that these other Grajewski’s were also from there. In no other way could I have been able to make the connection between two families living more than one hundred fifty miles apart.

Where to Go from Here

Are you researching your family and wondering how much more information might be available beyond what databases and beginner-friendly tools can provide? Are you stuck in your research, wanting to go further but unable to or unsure how to proceed? If so, please feel free to check out my website, www.lostrootsfamilyhistory.com, or contact me at 888-96-LOSTRTS (888-965-6787). You can also e-mail me by visiting https://lostrootsfamilyhistory.com/contact.

Add new comment